By Emilia Dworak, Mariasole Fusco, Artemii Grigorev, Zofia Idalia Torchała, and Alice Zambardino (@globalhistorylab)

Introduction by Elvira Viktória Tamus (@evtamus; evt27@cam.ac.uk), Teaching Fellow at the Global History Lab and PhD Candidate at the Faculty of History, University of Cambridge

Global History Lab (GHL) is an educational platform based at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Cambridge and offers two courses throughout the academic year. History of the World explores a wide array of peoples, societies, cultures, individuals, political events, military conflicts, and economic processes, to name a few, from the late Middle Ages until our present day. Qualitative Research Methods focuses on tools and methods necessary to conduct independent historical research. As learners at GHL, students and teaching fellows alike seek to create new narratives across global divides and train to become knowledge producers who think about the past globally, focusing on what brings different parts of the globe together and what keeps them apart. This article is the first in a series of three written by groups of international undergraduates enrolled in the Global Humanities degree programme at the Sapienza University of Rome (a GHL partner) that reflect on global phenomena, student life, diverse narratives, and what the world looks like now from their perspective – from the vantage point of Rome.

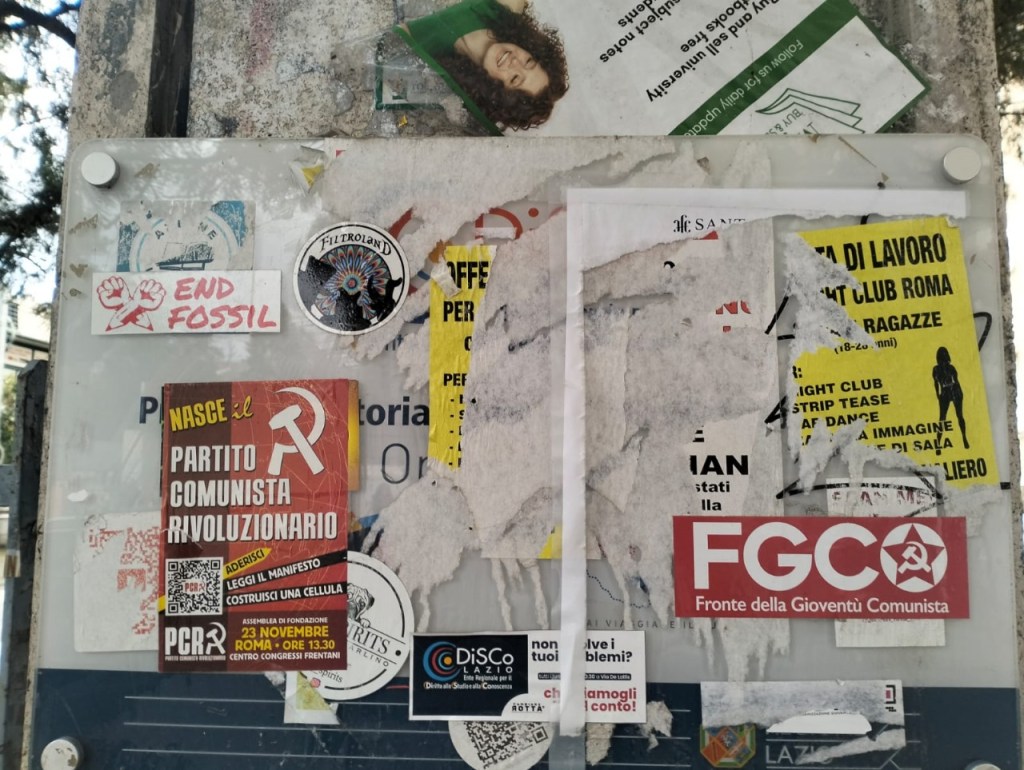

Read more: Echoes of communism: A cross-cultural reflectionThe first team have written a thought-provoking article on the colour red as a symbol of communism and the USSR. They were inspired to write about the reception of communism by the experience of walking through the Sapienza campus, where some places are always filled with posters. Those who come from countries that belonged to the USSR or the Eastern bloc, where communism is either banned or taboo, found the number of communist posters staggering. Their perception sparked a discussion with Italian students, for whom communist posters, symbols, and references are normal and the ideology of communism is an important part of history, society, and culture. What is powerful about the work of these students is their courage to compare their experiences, their willingness to consider differing arguments, and their ability to offer a concise conclusion: ‘we need to create a new symbolic language, one free from ghosts of the past’.

—Elvira Viktória Tamus

The Ambiguity of Red

The campus of Sapienza University of Rome is not a place devoid of politics. Students’ parties and societies promote their events, so much that some walls remind you of a colourful patchwork with bits of old posters. Some are blue, some white, some green. Some – many – are red, with stars and fists and hammers and sickles. Unsurprising to many Italians, these immediately catch other people’s attention.

Some of these symbols are somehow ambiguous. While they represent, undoubtedly, social struggle and hope for a better world, they are also the official symbols of a specific political entity – the Soviet Union. The USSR brought its people liberation from monarchy and free healthcare – as well as totalitarian dictatorship and mass murder; it was an embodiment of ‘communism’, yet never achieved it.

The message of those posters may aim to inspire ideals of equality and justice, but is that message clear at all? This ambiguity provoked a debate among us – students from Poland, Italy, and Russia – about how communism and its symbols are perceived in our countries. Each perspective reflects a distinct historical and cultural context, offering insight into the varied interpretations of communism in Europe today.

Communism in Poland: Trauma and Complexity

In Poland, communism evokes significant trauma. Years of living under an authoritarian regime left scars, with stories of food shortages and oppression vividly remembered. There was limited access to food, as all necessities had to be bought with stamps, meaning that every household had a specific amount of groceries allowed to purchase. Products such as hygiene items, clothing or home appliances were also difficult to acquire. Hospital workers were sometimes given rare ‘exotic’ food, such as oranges, as a holiday bonus. Yet inequality had not been erased as privilege and social position determined quality of life; some, more well-connected, families had better access to exclusive items. Members of the party retained a position of privilege. Housing quality was similarly uneven, with some families being luckier when assigning or inheriting accommodation than others.

The images of empty stores and monotone architecture still recall memories of a lack of sovereignty and the uncertainty of the country’s future. The idea of communism is associated with something foreign and oppressive, and most Poles would likely say they would not want to return. Yet communism’s legacy in Poland is not entirely negative. The regime provided jobs, housing, vacation programs for children, and accessible healthcare, which gave some sense of security during a time of global instability. However, it is not easy to use the word ‘communism’ neutrally. For those who lived through it, communism symbolises an era of immense struggle, sometimes in contrast with Western perspectives, which often approach the topic more ideologically. These contrasting perspectives continue to shape discussions on communism to this day.

Communism in Italy: Ideals, Culture, and Polarisation

In contrast to Poland, which endured the traumas of communism, Italy suffered most at the hands of a different ideology: two decades of fascist dictatorship left an indelible mark on the country’s history. In Italy, the Communist Party stood out precisely for its anti-fascist struggle, first expressed through the Resistance, which contributed to the development of democracy in the country.

Over the years, the Italian Communist Party lost its initial support and developed a negative connotation, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union. Today, the term ‘communist’ is used in a derogatory form, especially by right-wingers, to ridicule representatives of the Italian left, even when they do not have communist affiliation. This rhetoric is meant to subtly undermine and devalue their political stance – especially when ideals of social equality are brought up – leading to a polarisation of political discussion.

At the bottom of the ideological dichotomy between fascism and communism is a fundamental difference, as historian Alessandro Barbero brilliantly explains. While fascism contained in all of its forms the seeds of violence and oppression, communism – despite having resulted in horrific dictatorships – represented also the faith of people across the world who believed in ideals of justice, democracy, and equality.

For philosophers and intellectuals, communism was not just a political movement, but also a critical reflection on society. Antonio Gramsci, one of the leading Italian Marxist thinkers, is an example of how communist ideology can be linked to deep cultural research. ‘Man is above all else, mind, consciousness. That it is, he is a product of history, not of nature.”[1]

Nowadays, in Italian universities such as Sapienza in Rome, left-wing students, specifically those of communist ideology, distinguish themselves for spreading ideas about social equality, economic justice, and women’s rights through a cultural and political activism that aims to improve not only the environment of the university but society as a whole. For these students, the fight against global inequalities is far from the totalitarian perspective that

characterised communism in countries such as Poland or the Soviet Union.

Communism in Russia: Nostalgia and Disillusionment

Modern-day Russia is characterised by its authoritarian government and highly diverse and atomised population. A lack of true political debate and representation leads to some people not having any personal political position, since having one does not lead to anything.

Since Russia was both the place where the Soviet Union was created and destroyed, people regard it with a certain ambivalence. While some remember it positively or with nostalgia, others condemn it severely, depending on social strata and generation. Either way, there is a clear distinction between ‘communism’ and the ‘Soviet Union’, the former being an abstract ideology, widely known to be unreachable, while the latter is a specific state in Russian history. While ‘Soviet’ holds all the ambiguity one could expect, ‘communism’ seems to embody the spirit of failed utopia and successful injustice.

The inevitable rejection of the Soviet past leads to a feeling of distrust towards all ideologies, especially left-leaning ones. This distrust either fuels apathy or turns people toward mildly right-leaning liberalism – anything that promises individual freedom and prosperity as opposed to any collectivist or state-centric narrative. The communist party is not banned like it is in many post-Soviet countries, but it has almost no intelligible program and thrives off nostalgia of older generations. Meanwhile, the current government bases its ideology on the universal continuity of strong rulers – from Peter the Great, to Stalin, to Putin – in a certain cult of power beyond coherent ideology; Power without vision of the future, with only one goal – to execute itself.

Concluding Thoughts

The perception of communism today is shaped by history, geography, and personal experience. While in Italy some student groups use communist symbols to promote progressive ideals, to a Polish passerby these same symbols could be a painful reminder of political oppression. If we want a truly international political discussion – if we wish to be mutually understood – we need to create a new symbolic language, one free from ghosts of the past.

[1] Antonio Gramsci, inspired by Karl Marx’s work, Theses on Feuerbach (1845).

Image courtesy of the authors of this blog post and reproduced with their permission.