Interviewed by Jake Bransgrove, @Jake_Bransgrove

Historian Highlight is an ongoing series sharing the research experiences of historians in the History Faculty in Cambridge and beyond. For our latest instalment, we sat down with Sophia T. C. Feist (@stcfeist), a second-year PhD candidate at Corpus Christi College, to talk liveries, craft cultures at the courts of the Holy Roman Empire, and making as a form of historical inquiry.

Why don’t we start with the question about what you are currently researching?

I work on craft and material culture at the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the Early Modern period, and right now that means dress history. I’m working on a dissertation which focuses on dress and politics in the early-sixteenth-century Holy Roman Empire, writing about liveries and court tailors who made them.

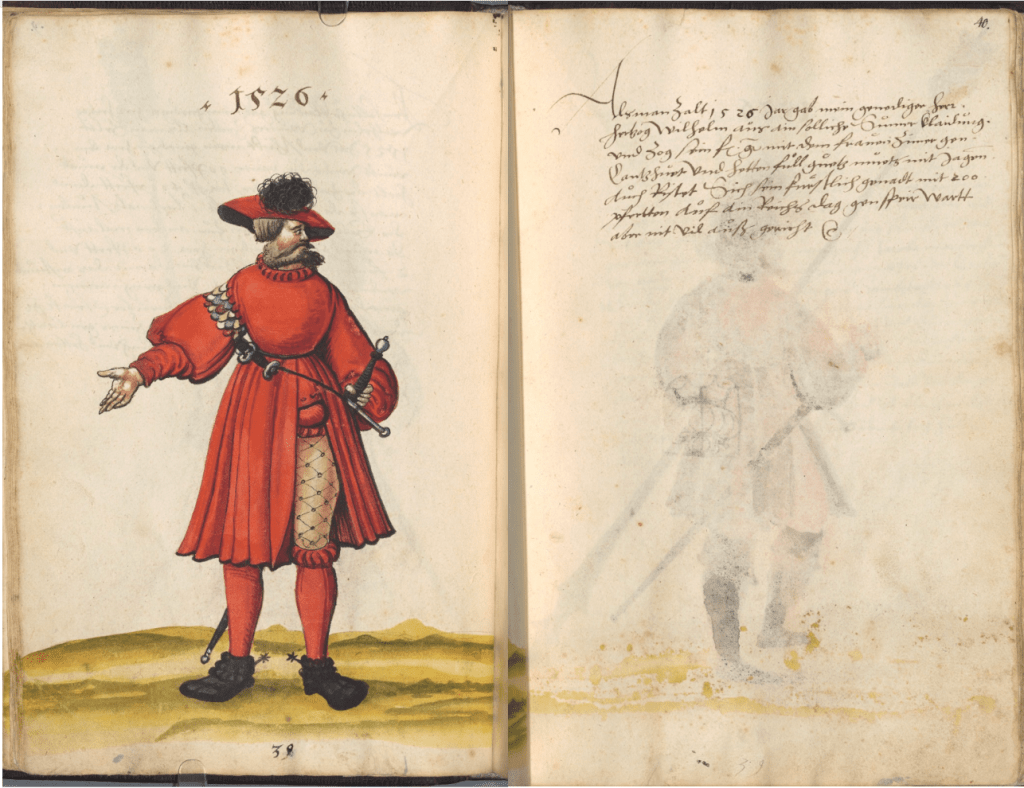

Liveries are basically uniform clothing that was issued by different rulers in the Empire, from duke’s to bishops to cities, as a way of demonstrating authority, creating groups, and, I argue, communicating specific political messaging. The liveries that I’m working on were not worn by servants; they were worn by nobles, and so it’s a different kind than you might imagine. I’m working on two surviving manuscripts which document liveries issued each year alongside a short political chronicle explaining what political and dynastic events occurred in the months when those liveries were worn. I’m also interested in the court tailors who made them – these manuscripts came out of court tailor’s workshops – and in how those court tailors worked, but also how engaged they were in the political processes in the Empire, in political self-fashioning, and decision-making.

How did you come to this specific topic?

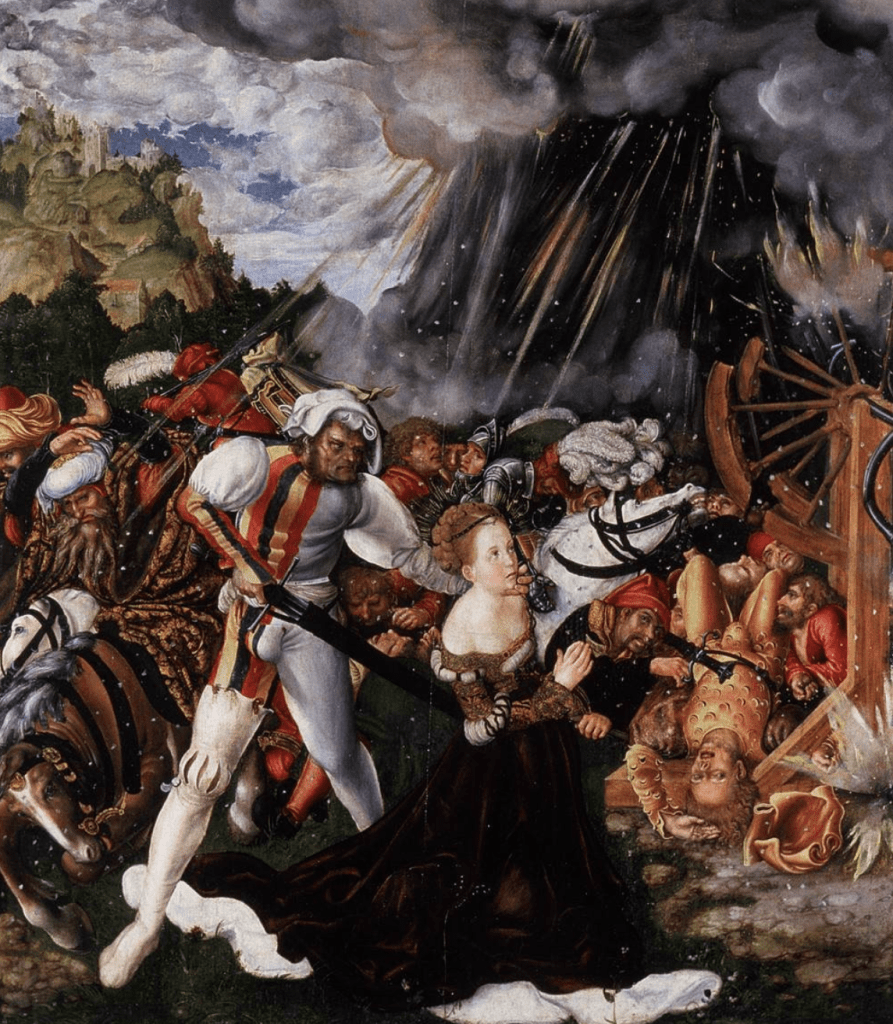

I came across one of the livery books when I was researching my Master’s dissertation, and I didn’t know what it was at the time. I was writing about a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1508), which is in Budapest. I was interested in the clothing in that painting. I thought it was unnecessarily complex; it was really strange to me. I dug into it and found that dress was essential to the narrative in the painting. In doing so, I was researching clothing at the Saxon court, because Cranach was the court painter for Frederick III (1463–1525). I came across a reference to this livery book which was made for the Saxon court and by the Saxon court tailor at the time. So that’s how I chanced across it, but I came to be focusing on dress more generally because I’ve always been interested in craft and how things are made. After my undergraduate degree I trained with a bespoke tailor for a year, so I have a bit of an understanding of how clothing comes together. I think I have more material literacy when it comes to textiles than most historians today, and that kind of made it easier for me to understand a lot of the material from the period, which can be very obscure and especially terminologically very hard to understand without a lot of background research.

Can you explain some of the more obscure types of dress that you work with? Things that a present day audience wouldn’t be familiar with but which you consider in your research.

A lot of it is just basic terminology to do with textiles and how clothing comes together, that often is still in use today (even if it means something different), but that you just wouldn’t know without a specialised education. Things like types of fabric, finishing processes, types of fastening, identifying different parts of a garment. These all would have been part of common vocabulary in the sixteenth century for people who were commissioning their own clothing and who lived in a very textile-centric economy, but aren’t familiar to people today and are often misused or have changed in meaning in the intervening centuries. You have things like words describing different types of wool fabrics, which get mixed up quite quickly. Worsted is an example (or ‘woosted’, as it sometimes pronounced). It fundamentally describes a way of spinning yarn, but it’s also used to describe fabrics made with that kind of yarn and now sometimes fabrics which look similar to fabrics made with that kind of yarn, but it also describes a thickness of yarn for knitters and crocheters and that’s how it’s most often used today. If you haven’t spun before you’re not really going to understand the difference between those terms and what’s meant by them and that’s important background knowledge that you have to develop before you can work on this kind of material.

Thinking about your ‘material literacy’ and also the way in which you go about dealing with these subjects in your work, is there any way that you think you are uniquely attempting to demystify these subjects, or is it simply a case of explaining them all the page?

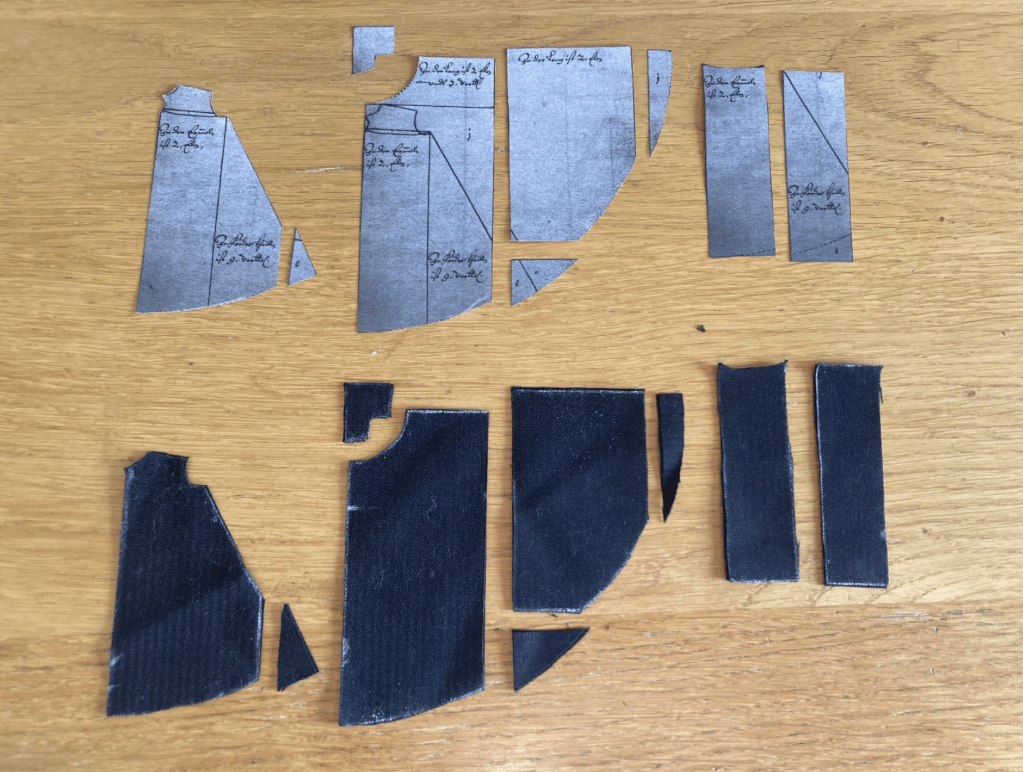

I am hoping to create a reconstruction of one of these liveries as (probably) the final chapter in the dissertation, and that’s something I’m starting to work on now. I think that it’s really essential to the research but there are all so a lot of people in the field who probably won’t think so, and so I’m making sure that the rest of the dissertation can stand independently of it. But I’m basically going to reconstruct one of the livery illustrations from the book into a livery, and that’s important because these drawings were essentially used as instructions – probably made by tailors, though illustrated by court painters, they were then sent out to a local tailor with the materials in question and the tailor would have to then make a pattern and assemble the garment based on this drawing as a set of instructions. That’s how it’s perceived now. That’s the agreed on – I’m still going to call it a hypothesis – for how these drawings functioned.

There are individual sheets which survive in archives across Germany which are evidence of how these were sent out and distributed, and also archival records of court painters including Cranach being commissioned to make these livery illustrations. I’m going to test how these illustrations functioned by trying to reconstruct them and ask how useful they were for court tailors; what information actually is in them; and, especially, what information was prioritised. What that essentially means is that information had to be uniform across all of these garments, being made by 100 different tailors trained in 100 different workshops. What really had to be identical and what was a little bit more flexible? So I’m basically going to reconstruct a livery as an experiment about process to try and see how these illustrations might have been used and what I can learn about them – reconstruction is a form of slow looking.

How do you think about your identity as a scholar? How would you try to define yourself?

That’s a mean question! I think that that’s quite challenging and, as a PhD student who’s beginning to publish (as we all are trying to), something you really have to think about is the bigger picture – where you fit into things. All of my background and training have been in art history and I’ve been very happy with that but now I’m sort of working in history which is quite different and I’m still figuring out where I sit between those two fields and whether I have to decide. But I think what I find most important in my research and the threads that I want to pull out are craft cultures, cultures of making, and artisans, and I’d like to approach that ideally in an interdisciplinary way but from whatever angles I can. I think that means looking not just at scholarship from history (about the social and cultural context and impact) or art history (about the objects themselves and what we can learn about making), but also looking at conservation, technical art history, archaeology, and other fields, and seeing how I can bring a fuller picture to this.

What’s struck you the most about the move from more of an art historical setting to an historical one?

I think how much it matters – I didn’t think it would. I’ve been surprised in the last year, since I started my PhD, by the ways in which disciplinary boundaries have crystallised for me. I think there are a lot of quite subtle cues and differences in the ways in which academics write and communicate. I’ve also found it surprising how little some scholars are aware of the scholarship happening at the same time, often focusing on the same themes and concepts, in other fields, and I think more communication between those fields would be very fruitful – although I’m not really saying anything new there, am I?

Why do you practise history?

I’m going to answer it by going back in time, because I’m a historian. I’ve always asked myself where things came from and that’s the first approach I take to try and understand them. I always have thought that by understanding how things developed you can understand what they’ve come to be, but I think history is also really compelling to me because it is (contrary to what I just said) such an interdisciplinary field. It encompasses so much. I’m a very curious person and I want to know how things work, and when you study history you can really study anything else inside that realm. You can explore so many different topics and concepts and build a fuller, richer picture of them. I think that history is important. It can tell us so much about ourselves.

Are there historians’ whose work you particularly like or admire?

I find that question quite hard to answer. I can list a couple for you, but I’m not sure it’s going to be very elucidating as a response. One of the first historians I really liked was Simon Schama. He does a really good job of being honest about his limitations, rigorous in his methods, and being very well-researched, whilst still writing in a really compelling way. I think that’s something that we sometimes don’t value enough in history education.

I admire a lot of the pioneering scholarship that’s happening in dress history right now. I think a lot of it’s quite brave, especially at a time when there is a lot of career precarity, and while there is some motivation because of that to expand and try something new it also means that’s sort of dangerous especially when you’re functioning in a field that’s often not taken seriously. Sarah Bendall, for example, and her book on foundation garments, Shaping Femininity (2021), are particularly inspiring. She does a lot of reconstructions, which takes a huge amount of effort and labour, and is quite a risky thing to do. But she does it in a really thorough way.

They aren’t technically historians – and they’ll tell you this themselves – but I admire conservators and the research they do, too. The time they spend with objects and the way they look closely at them isn’t given enough credence by many, but it makes a really important contribution and I think their scholarship deserves more attention in the field.

Let’s come back to Schama and use him as a jumping off point. You mentioned his writing, and you mentioned his methods of communication, and the importance of that to you. What do you think good historical writing is?

Well, because you bring up Schama, I do think that good historical writing should be, for want of a better word, beautiful. I think that looks very different from beautiful writing in, say, fiction or even in popular non-fiction, but I think that there is a way in which you can be really precise and clear and also very elegant and vivid in historical writing that makes a huge difference. As anyone who works with primary source material will tell you, the form and medium of communication can be as important as the content, and I think that stands for historical writing as well. It doesn’t hurt that it makes it more compelling as well to read. I also think that humility is very important to historical writing. It’s important for historians to acknowledge our limitations and acknowledge ambiguity and uncertainties, even if that sometimes comes at the expense of your argument. The best history I’ve read has been history that acknowledges the uncertainties in the question still open and the limitations of the material.

I want to come back to you now, and where we are now, and ask what you think Cambridge offers you as a scholar. What’s unique about being here as a postgraduate student?

Well, the focus on material culture is important and the supervision structure can be really beneficial, also for the instructor who’s having a conversation about the material with an undergraduate in a fresh way. Having access to the Fitz is great and there are a lot of resources in the UL, but I think the most important thing about my experience has been quite atypical for a PhD student, in that I’ve found a really strong community of other scholars and students. My successes so far – if you can call them that – wouldn’t have been possible without that kind of non-competitive support from my peers who are mostly in my supervision group.

A final word: can you tell me about any interesting experiences in the archive?

I want to tell you about an interesting experience I had in a museum. This goes back to my Master’s dissertation. I mentioned I was focusing on this one painting, The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine by Lucas Cranach the Elder, and it is in Budapest. It’s a famous painting, probably made in competition with Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), but it hasn’t really been researched very much, partly because it’s quite hard to find. I was looking for the collection where it was held because I wanted to visit it and see it in person – because that makes quite a difference to research – and I called a bunch of museums in Hungary, fruitlessly. I looked everywhere to try and find out where it was displayed, because objects from the same collection were being shown in multiple locations. Their main buildings were under construction and I thought that I’d found the painting in an online tour of a museum in a small town outside Budapest, and I was really proud of myself for having found it! I booked a flight and went there for a weekend, and at 8AM on a Sunday I took a train to this town to try and find this painting. I think it was in a university museum. I went to the museum and they had to open up for me (because no one else was there) and turn on all the lights. The women there had no idea what I was talking about, but I went and finally found the painting after this very long journey – and it was a framed print on the wall… In the end, I got very little out of that other than a good story and a nice weekend drinking Hungarian wine by the Danube!

Cover Image: Feist at her Cambridge matriculation in October 2023 (Photo: Shannon Paige)