By Andreas Nabil Younan (any21@cam.ac.uk)

How does one write the political history of an authoritarian regime, where access to

state documents is restricted for national security reasons and censorship has been

widespread?

Egypt has been under strict military rule since the republic’s founding in 1952,

following a coup d’état by the “Free Officers” movement against the British-backed

monarchy. President Anwar Sadat (r. 1970-1981), a Free Officer, introduced a multi-

party system in 1976, and soon the new regime faced real parliamentary opposition

for the first time. Islamists of various factions—including the banned Muslim

Brotherhood—were allowed to run for parliament despite their primary goal of

dismantling the legal system and rebuilding it based on Islamic values, ultimately

aiming to rule by Islamic law. A story that largely remains untold.

Scholarship on politics in post-1952 Egypt has primarily relied on memoirs and

newspaper coverage, published mainly by state-controlled publishers that seldom

provided space for oppositional voices. In the late 1970s, during the so-called

“Islamic revival”, an Islamic press engaged in the struggle over history and the

political narrative, but only with limited success due to banning, censorship, and

imprisonment—especially after the assassination of President Sadat by militant

Islamists in October 1981. However, since at least 1924, every word uttered from the

podium under the dome of the Parliament has been meticulously transcribed in

“minutes” (maḍbaṭa, pl. maḍābiṭ), making it an invaluable—and, most importantly,

uncensored and unfiltered—source documenting parliamentary life. An interesting

case is law no. 63 from 1976 called “prohibition on alcohol drinking”, which is a

criminal offence punished with flogging in classical Islamic jurisprudence. The law

was considered the first Islamic law enacted. However, the law did not ban alcohol

drinking; it merely restricted it to hotels and other places with alcohol licenses, and it

allowed alcohol to be sold to foreigners. In practice, the ban was not enforced, and

liquor continued to be freely served to Egyptians. The minutes reveal that the original

bill, presented by Islamist Maḥmūd Nāfiʿ, sought a total ban on alcohol consumption,

but the regime ultimately prevailed in Parliament.

During the so-called “golden age of opposition”1 in the late 1970s, oppositional MPs

became increasingly aware of the pivotal role of the minutes in documenting their

struggle against a too-powerful opponent, the Egyptian regime. In the words of a

prominent figure, Maḥmūd al-Qāḍī, who, during a debate, said: “I am speaking for

the minutes and history”.2 In Islamist oppositional circles, it was widely believed that

state-controlled media deliberately kept their activities in Parliament under wraps,

and sometimes even twisted their words to defame them.3 They tried to counter the

media blackout, or the “silence conspiracy”4 , by publishing the minutes through the

Islamic press.5 One example is ʿĀdil ʿĪd, an independent MP from 1976 to 1979, who

pieced together his political memoirs, “The Minutes Speak”, using only excerpts from

the minutes. The book reveals that the debate on banning alcohol consumption

continued in 1977, with ʿĪd himself presenting a bill for a complete ban against

drinking, production, sale, and circulation.6 However, the bill was buried in one of

Parliament’s many subcommittees, a known regime tactic. In the book’s introduction,

ʿĪd, a lawyer, explained how the minutes serve as a “defence memorandum” in the

regime-led campaign against the opposition.7 His defence, however, proved

insufficient, and he ended up imprisoned together with more than 1500 other

oppositional figures in September 1981, an action many believe contributed to

President Sadat’s assassination a month later.8

The parliamentary minutes remain an inaccessible and untapped source that could

unveil the history of parliamentary life in modern Egypt and challenge the regime-

controlled narrative. Let the minutes speak, so that we can write history.

Notes:

- ʿAbd al-Samīʿ, Jamāl. 1983. Maḥmūd Al-Qāḍī: Najm al-ʿAṣr al-Dhahabī Lil-Muʿāraḍa Bi-l-Wathāʾiq

Wa-l-Shuhūd. Cairo: Tawzīʿ al-Ahrām. ↩︎ - Ibid., p. 72. ↩︎

- Rāḍī, Muḥsin. 1990. Al-Ikhwān al-Muslimūn Taḥta Qubbat al-Barlamān. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Cairo: Dār al- ↩︎

- ʿĪd, 1984, p. 4. ↩︎

- One example is Rāḍī, 1990. ↩︎

- ʿĪd, 1984, pp. 108-112. ↩︎

- ʿĪd, 1984, p. 4. ↩︎

- Ismāʿīl, Ṭāriq. 2016. ‘fī dhikrā qarārāt sibtambir: ʿādil ʿīd.. al-muʿāriḍ al-sharīf alladhī rafaḍa al-

wizāra’. al-Ahrām. 13 September 2016.

https://gate.ahram.org.eg/daily/News/192022/62/550697/الاسكندرية/فى-ذكرى-قرارات-سبتمبر–عادل-عيد–المعارض-

الشريف-ال.aspx. ↩︎

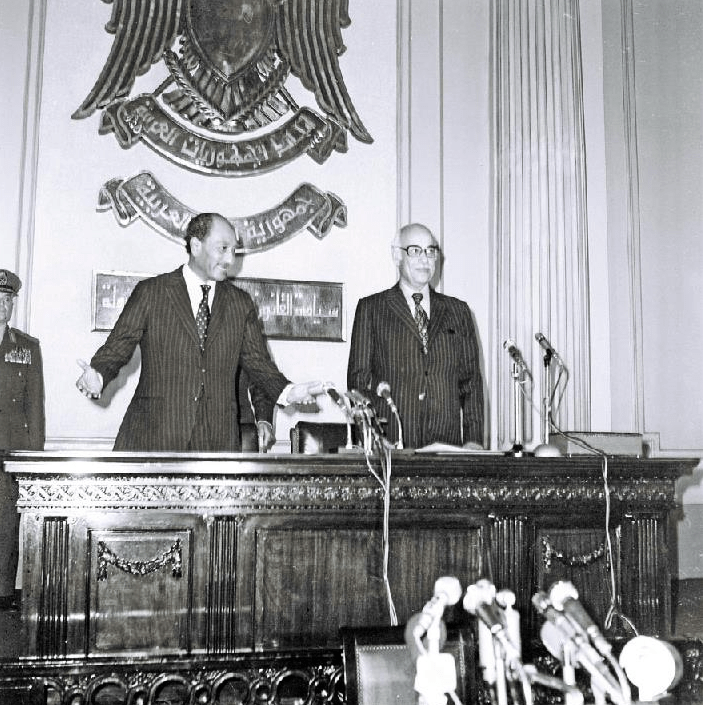

Image: Anwar Sadat-Egyptian Parliament-1977: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anwar_Sadat-Egyptian_Parliament-1977_%2809%29.png