By Giles Ockenden

From a 21st Century viewpoint, American Prohibition seems a fascinating yet alien episode. That the United States banned the production, sale, importation and transportation of alcoholic beverages between 1920 and 1933 might be difficult to imagine today. Prohibition’s success in fighting the consumption and demand for alcohol can be debated, yet the case study of one minor international scandal serves to show that Americans’ thirst for alcohol was far from quenched. This scandal, which has gone unnoticed in the historiography, reveals a variety of trends – most obviously Americans’ ingenuity in finding ways to acquire alcohol. Indeed, the episode is as distinctive as it is revealing; Prohibition laws were broken and a minor scandal was precipitated by none other than a cruiser of the German Navy.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the fledgling post-war German Navy (the Reichsmarine) was equal parts controversial and anaemic. In practice, restrictions under the Treaty of Versailles and the scuttling of the fleet at Scapa Flow in 1919 meant that the German Navy, which had been built to challenge the Royal Navy, was from 1920 little more than a coastal defence force. This was undoubtedly a fall from grace; while the navy had been a pre-war technological marvel, by the 1920s there were incidents of German sailors being killed when neglected old boilers on ships exploded. Simultaneously, the Reichsmarine was a near-constant source of controversy. Its sailors had mutinied in November 1918, precipitating the German Revolution, and Communist sailors (the Volksmarinedivision) were central to the revolutionary street-fighting in Berlin in late 1918 through 1919.

More serious was the involvement of naval elements in the radical right-wing Kapp Putsch in the early 1920s, where naval Freikorps brigades spearheaded the coup and Vizeadmiral von Trotha had pledged the Navy’s support to the Putschist government. Thereafter, the Reichsmarine maintained a reputation as a hotbed of reactionary politics, and the naval budget was a repeated source of heated debate and personal attacks in the Reichstag between pro-naval and anti-naval deputies. In an attempt to rectify the Reichsmarine’s image, the naval leadership re-instituted world tours by German warships to foreign ports in the mid-1920s. Ironically, pro-naval voices claimed these trips showed how the navy could boost, not undermine, Germany’s image abroad.

In 1926, the cruiser Hamburg eventually found itself on one such trip, touring the world and eventually reaching the port city of San Pedro in the United States. Here began a strange episode. This was the first visit of a German warship to an American port since 1914 and, consequently, tourists flocked to view the ship. According to a report by the Captain, some of the American visitors were determined to take advantage of the situation; a supposedly ‘enormous’ crowd surged to the canteen to try and buy beer, which was sold to approximately thirty people at $1 a bottle (or $17 today – supposedly not at a profit). Unfortunately for both the crew and the tourists, American prohibition agents had come aboard in plain clothes and reported this to the authorities. The US State Department promptly raised it with the German Embassy, which launched its own investigation; the episode concluded with the ‘exemplary punishment’ of two petty officers from the Hamburg.

Quirky though this incident sounds, the media reaction in Germany revealed just how polarised and fragmented the German press truly was. Depending on the paper, readers received near-completely contradictory versions of events. Centrist publications, such as the Vossische Zeitung, Berliner Morgenpost or the Bavarian satirical journal Simplicissimuss treated the event as a non-issue. Even in the centre, however, there were divergences: nationalist frustration in the Germania contrasted with the more critical view of the left-leaning Berliner Tageblatt.

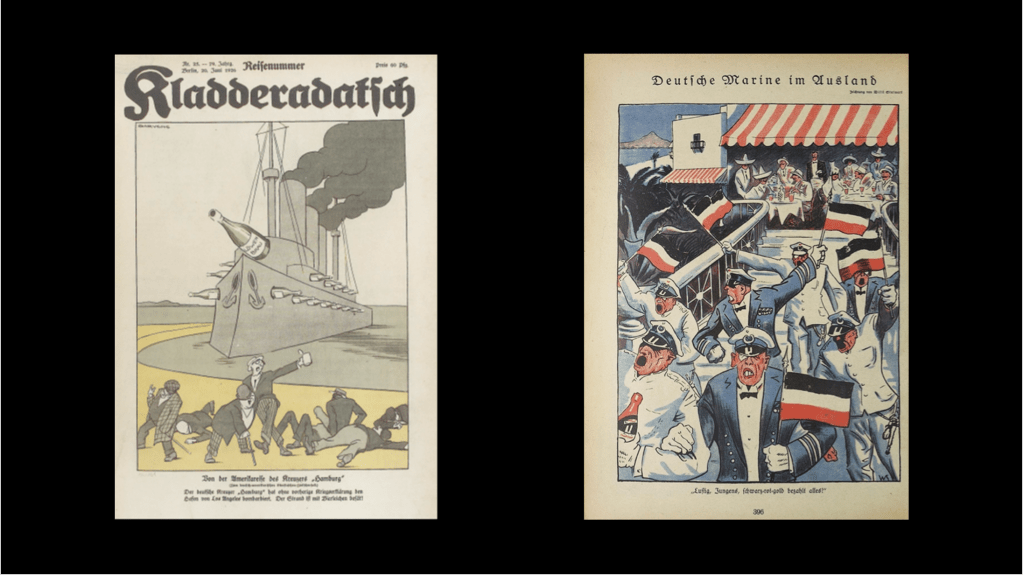

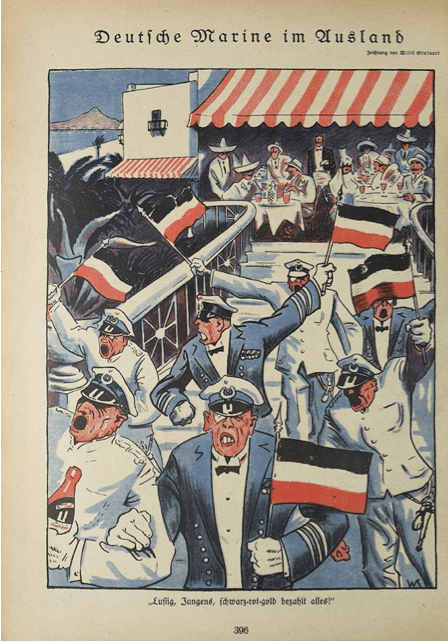

Yet the greatest contrast was between right and left. On the one hand, the right-wing press, such as the Kölnische Zeitung, Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger and Hamburger Fremdenblatt raged against the unacceptable violation of German sovereignty in the authorities’ undercover surveillance on board the cruiser. By contrast, leftist papers launched tirades against the nationalist right and the equally nationalist navy: Vorwärts, for instance, claimed that the German navy was ‘one of the most superfluous things in the world’, and argued that the ‘extraterritoriality’ defence was utterly absurd. Republican and nationalist satirical journals were similarly polarised. On the one hand, the nationalist Kladderatasch mocked the Americans by portraying the cruiser bombarding the states with alcohol (Figure 1), whilst the Social Democratic Lachen Links attempted to convey the vile spectacle of nationalistic, brutish Reichsmarine sailors abroad. (Figure 2)