By Zoë Jackson (@ZoeMJackson1)

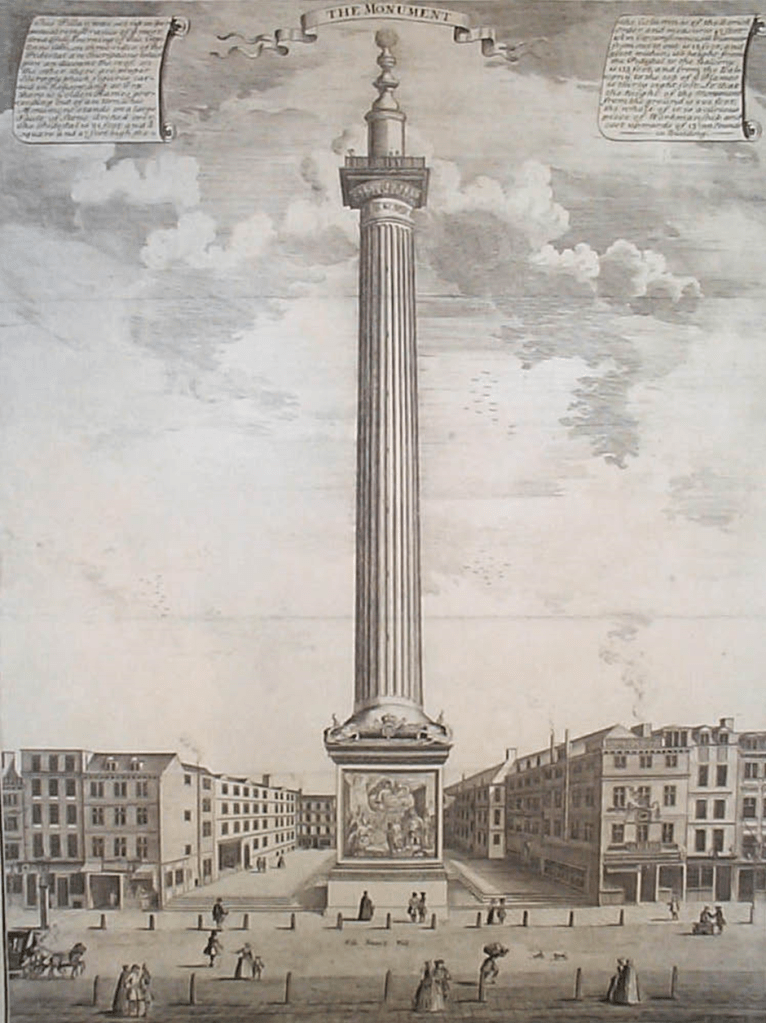

If you have ever disembarked off the London Tube at Monument, you have probably walked past the memorial from which the station gets its name. This 202-foot (61 metres) high column was built to memorialise the 1666 Great Fire of London, which destroyed thousands of houses and numerous churches in central London. But it also encapsulates the processes of memory and commemoration, and how these processes are shaped by the politics of the day.

The Monument was built between 1671 and 1677 as a commemoration of the fire and the damage it had done. In 1681, however, the Monument was modified with two new inscriptions. An English inscription described ‘the most dreadful Burning of this Protestant City, begun and carried on by the treachery and malice of the popish faction’ as part of ‘their horrid plot’ to eradicate Protestantism and ‘introduce popery and slavery’. A Latin inscription expressed a similar sentiment, while warning of the continued Popish threat.[1]

The addition of the inscriptions reflected the charged political and religious atmosphere of later seventeenth-century England. The late 1670s and early 1680s had witnessed the Popish Plot crisis, a purported but likely fabricated Catholic plan to assassinate King Charles II and reestablish Catholicism in England, along with the Exclusion Crisis, in which Parliament debated whether or not to exclude Charles’s Catholic brother, then James, Duke of York, from the succession.[2] Further, the Great Fire reinforced widespread fears and associations of fires with Catholics.[3]

There were challenges to the inscription from its instalment, and they were covered up when King James II came to power in 1685. However, the texts were thereafter reinstated following the Glorious Revolution, which forced James to flee, and put King William III and Queen Mary II on the throne. The controversial inscriptions were only permanently removed in 1830.[4]

Peter Hinds characterises the Monument as a ‘civic palimpsest’.[5] The history of the Monument reminds us that all objects of commemoration are a product of their time, and record much more than just the events they were designed to memorialise.

References:

[1] Peter Hinds, ‘The Horrid Popish Plot’: Roger L’Estrange and the Circulation of Political Discourse in Late Seventeenth-Century London (Oxford: Printed for the British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 361, 363.

[2] See Hinds, ‘The Horrid Popish Plot’ for an examination of the Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis, particularly in relation to contemporary print.

[3] Ibid., ‘The Horrid Popish Plot’, Chapter 10 (pp. 361 – 396).

[4] Ibid., ‘The Horrid Popish Plot’, pp. 384–395.

[5] Ibid., ‘The Horrid Popish Plot’, p. 395; According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a palimpsest is ‘A parchment or other writing surface on which the original text has been effaced or partially erased, and then overwritten by another’; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. ‘palimpsest, n., sense 2.a’, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1100401456.