By Marlo Avidon (@marloavidon.bsky.social)

While today, families gather around the tree to open gifts on Christmas morning, in sixteenth and seventeenth-century England Christmas Eve and Day were a comparatively solemn affair. That did not mean, however, that families, friends, and their patrons did not exchange gifts over the holidays!

Rather than Christmas morning, New Year’s Day was traditionally regarded as the main opportunity for early modern men and women to exchange gifts. Members of early modern society used the first day of the new calendar year as the opportunity to reward dedicated members of household staff, honour interfamilial bonds, or even try to increase their favour at court and climb the social ladder. New Year’s Gifts could take a variety of forms, as reflected in many volumes of diverse domestic account books. Many courtiers, such as the diarist John Evelyn, noted giving away financial gifts to their own household staff as well as while attending court, bestowing small tokens of appreciation onto various porters, grooms, and footmen.

However, for those interacting closely with the crown, the exchange of gifts on New Year’s Day was a powerful tactic for enforcing social order, court hierarchies, or enforcing ties of patronage and loyalty.[1] At the Elizabethan Court, compiled rolls of New Year’s Gifts for the Queen between 1559-1603 included a diverse variety of items.[2] As example, imported textiles and other luxury goods from England’s burgeoning colonies bestowed upon her by courtiers, including tropical fruits and East Asian silks, highlighted the nation’s growing prosperity. Importantly they also commemorated and honoured the Queen’s position as the head of a prosperous nation and vibrant court. [3] These politically charged gifts gifts could also take on more ephemeral forms – in 1635, a poem by Ben Jonson was performed by Nicholas Lanier as a New Year’s Gift to King Charles I. The song, an integral part of Caroline masque and court culture, celebrated the King as a ‘shepherd and husbandman to his nation.’[4] Once again, the exchange of New Year’s Gifts helped assert royal authority and demonstrated both Jonson and Lanier’s loyalty to their royal patron.

While not the Christmas gifts we know and love today, the use of New Year’s Day as a time to reforge or reinforce vital social, cultural, and political connections recontextualises the importance of gift exchange in early modern society. It ultimately reveals that money, material goods, or performance art could set the stage for future interactions at court for the year to come and shape a courtier’s relationship with the crown.

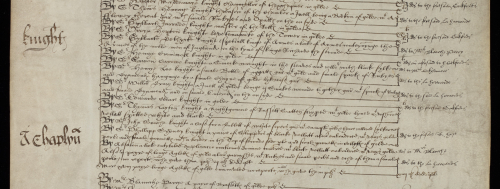

Image Credit: Detail from New Year’s gift-roll of Elizabeth I, 1 January 1567: Add MS 9772, f. 10v, British Library, Accessed via https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2022/01/celebrating-the-new-year.html

[1] Gillian Darley, John Evelyn: Living for Ingenuity (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2006).

[2] J.A. Lawson, The Elizabethan New Year’s Gift Exchanges, 1559–1603 (Oxford: British Academy, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, 2015). doi:10.1093/actrade/9780197265260.book.1

[3] Susan M. Cogan, ‘Flowers and Gift Culture at the Elizabethan Court’, in Susannah Lyon-Whaley, ed. Floral Culture and the Tudor and Stuart Courts. Early Modern Court Studies. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024).

[4] ‘A New Year’s Gift sung to King Charles. 1636’, In Tom Cain, Ruth Connolly (eds.), The Poems of Ben Jonson (London: Routledge, 2021)