By Matt Ryan (follow on Twitter/X @heggledepeg)

The minutes of the Stationers’ Company court often follow a predictable script: legislation is discussed, disputes heard, fines issued, and debts settled. Occasionally, however, surprises appear. Squeezed onto the bottom of an entry from March 1633, for instance, is a record for an unlisted sum of money paid ‘To Mr Blount in his Sickness.’ While the Company regularly extended poor relief to its struggling members, this is not a name you’d expect to see listed as a recipient.

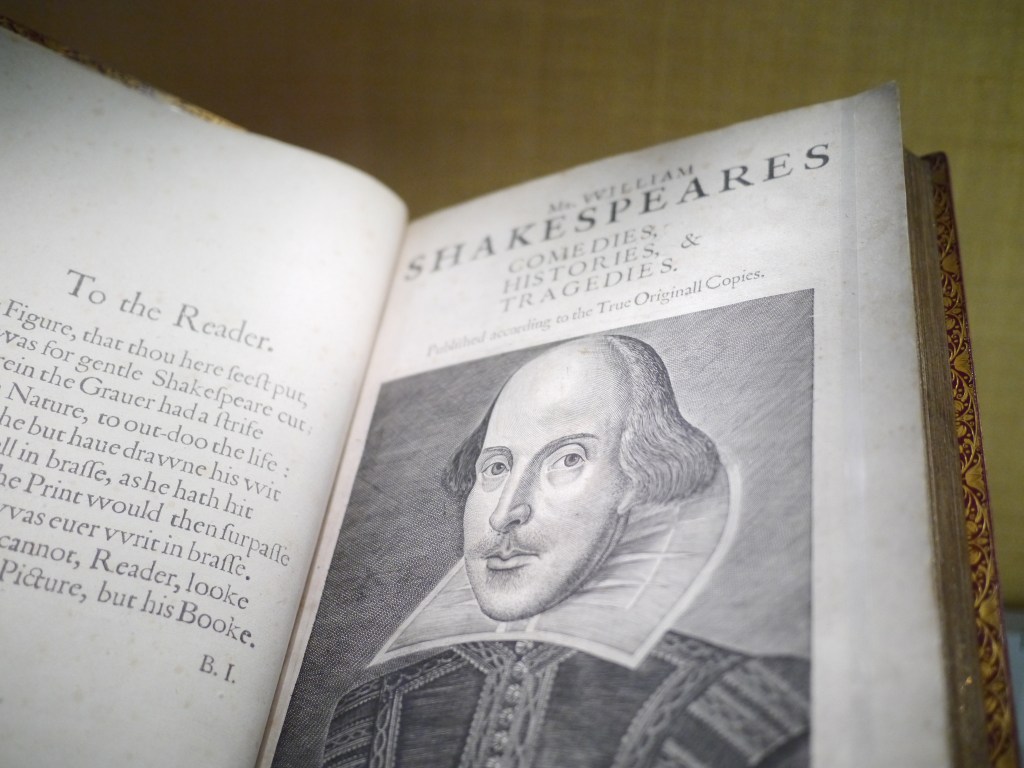

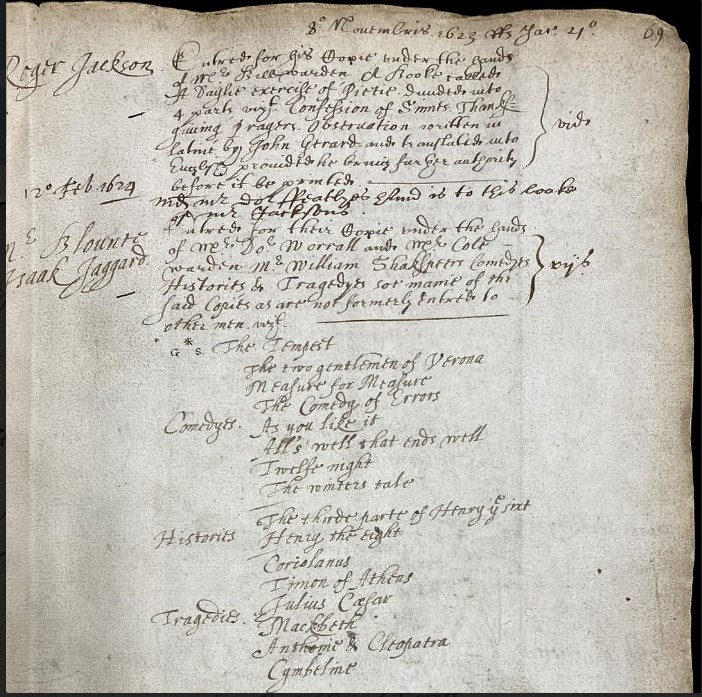

Edward Blount was a wildly successful figure in the Elizabethan and Jacobean book trade. Together with his collaborators at the Black Bear bookshop, he published several contemporary best sellers. The poetry of Christopher Marlowe, James I’s Basilikon Doron and the plays of John Lyly were all lucrative titles in an overstuffed marketplace. Blount also took a keen interest in continental European literary developments, introducing English readers to the Essayes of Michel de Montaigne, and Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The publisher’s impressive inventory has led many scholars to identify Blount as a ‘key figure in the development of a vernacular literary tradition at the start of the seventeenth century.’[1] Most memorably, Blount was also one of the financiers behind Shakespeare’s First Folio (1624).

After the mid-1620s, however, Blount largely disappears from the historical record, and the appearance of his name, a decade later, in a list of poor relief payments proved to be his last. So, what happened? Evidently, his career took a nosedive, and even with such successes to his name, this is not entirely surprising. The early modern book trade was a precarious place to make a living, and even the most basic print project came with an eye-watering amount of shopping. First, an author’s manuscript was purchased. Then, a fee agreed with a printer before the cost of ink and paper were added to the bill. Licensing fees came next, and any extras – engravings, woodcuts, coloured ink – each had their own price tag. With this kind of capital outlay at stake, any chance of significant returns required deep pockets and a keen eye for the tastes of the book buying public. Given these occupational hazards, at one time or another, many sixteenth and seventeenth century publishers found themselves in debt.

Yet, how did Blount end up in the red? Most accounts of his career argue that the cost of producing Shakespeare’s collected plays must have been to blame.[2] The First Folio was financed by several agents, and while we have no way of knowing how they divided their contributions, the total production costs were probably around £250.[3] By comparison, Blount’s bookshop, ideally located in St Paul’s Churchyard, is priced in its deed of sale at about £8 per year.[4] While the cost of the First Folio was undoubtedly a large sum, it is unlikely that such a canny operator would have entered the Shakespeare project unprepared to mitigate its financial impact on his livelihood. In fact, on a recent trip to London Metropolitan Archives, I came across a series of documents that suggest the root of Blount’s financial troubles lay elsewhere.

A report of a Court of Chancery case tried in October and November 1623 suggests that Blount was owed as much as £2,000 by one Roger Roydon.[5] Roydon’s debt seems to have gone through various courts for several years and reached a crisis at about the time the First Folio arrived in London’s bookshops. From what I can gather, the debt did not originate with Blount. Instead, it was created by a fellow bookseller Richard Bankworth, who loaned Roydon £1,000 in 1614. Bankworth was married to Roydon’s sister, Elizabeth, and to lend such a large sum, he must have assumed his brother-in-law was good for the money. Before long, however, things became complicated. Months after issuing the loan, Bankworth died, and his estate was left to his widow. Elizabeth stayed active in the book trade, and steered the business well, issuing several lucrative titles. She even appears to have lent a hand to her brother Roydon, apprenticing him in 1615. If this was an attempt to help Roydon pay what he owed, it appears to have failed, as in 1618, the debt had grown further. It was in this year that things took another turn; one that would ultimately spell disaster for the protagonist of our story.

In May 1618, Elizabeth Bankworth married Edward Blount. With Roger Roydon’s debt now on his slate, Blount – riding high on his successes – launched legal action. He could not have foreseen what was in store. Five years of legal wrangling followed, with Roydon managing to evade punishment at every turn. Battered by legal fees, court records from October 1623 paint a bleak picture of Blount’s financial situation. Desperate for a solution, he is recorded as having ‘done his utmost endeavors to get in the said debt,’ but still ‘resteth unpaid.’[6] A month later, Blount took his case to the Chancery, and Roydon finally agreed to pay £1,400, offering his land in Wales as guarantee. At last, it seemed, Blount’s woes were at an end. But, six months later, a survey of these lands returned disastrous news: they did not belong to Roydon. With the case still unsettled, it appears again in the Chancery records in April 1624, at which point a beleaguered Blount declares himself ‘utterly… defrauded & defeated.’[7] Later that year, Blount was forced by the Stationers’ Company to sell his most lucrative licences and surrender several financial benefits.[8] It seems then, that Roydon’s astronomical debt was too much for his brother-in-law to bear.

Shedding new light on Blount’s sudden disappearance from the landscape of the book trade, this evidence reveals that a costly intra-family feud, rather than a wobbly business model, likely led to his decline. The final mention of his name in the Stationers’ Company court books was almost certainly inscribed after his death and marks the turbulent end to a long career. As such, the words ‘To Mr Blount in his Sickness’ reflect on the precarious realities of life in the book trade and stand as a poignant epitaph to an important and often forgotten early modern print agent.

Further reading:

- Ben Higgins, Shakespeare’s Syndicate: The First Folio, its Publishers, and the Early Modern Book Trade (Oxford: OUP, 2022).

- Chris Laoutaris, Shakespeare’s Book: The Intertwined Lives Behing the First Folio (London: William Collins, 2023).

- Emma Smith, The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2016).

[Cover image: Shakespeare’s First Folio. Credit: Creative Commons]

[1] Ben Higgins, Shakespeare’s Syndicate: The First Folio, Its Publishers, and the Early Modern Book Trade (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022) p. 45.

[2] Eric Rasmussen, ‘Publishing the First Folio’ in: Emma Smith ed. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s First Folio. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016) 18-29; p.23

[3] Peter Blayney, The First Folio of Shakespeare (Washington, D.C.: Folger Library, 1991) p.26.

[4] Blount’s rent is noted in a deed of sale included in Husting Roll 303 at the London Metropolitan Archive (Item 40, CLA/023/DW/01/302).

[5] Details of the case taken from three related documents: Blount’s Bill of Complaint to the Court of Chancery (The National Archives [TNA] C 3/333/25), and two statements by the court clerks in the Entry Books of Decrees and Orders (TNA C 33/145, fol. 415v–416r; TNA C 33/147, fol. 663r–v).

[6] TNA C 33/145, fol. 415v.

[7] TNA C 3/333/25, fol. 24r.

[8] William A. Jackson ed., Records of the Court of the Stationers’ Company, 1602–1640 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1957), p. 100.