Thomas Maidment, interviewed by Jake Bransgrove

Historian Highlight is an ongoing series sharing the research experiences of historians in the History Faculty in Cambridge and beyond. For our latest instalment, we sat down with Thomas Maidment, a second-year PhD candidate at Selwyn College, to talk about his research on visions of a European union in interwar Britain, in a conversation ranging from Brexit to Oswald Mosely, and Thomas Hardy to Aristotle.

Thomas, can you tell me what you’re currently researching?

My PhD focuses on visions of a European union in the interwar and immediate post-war period from members of what we might call the ‘British right’. ‘The Right’ is broadly conceived – it includes Liberal Conservatives on the one hand all the way to Fascists on the other, and every hyphenated form of right-wing ideology in between. Basically, it’s looking at how these people, in the wake of the First World War, started to think about the international order; the idea of perhaps a federated Europe, or something more fanciful, more loose. So you can end up looking at very detailed political schemes or you can also be looking at cultural and racial conceptions of what ties Europe together, and the idea that Britain and Europe perhaps have a shared destiny.

And what’s the prehistory of your interest in this topic?

Well it comes from a strange place. When I was an undergraduate I originally wanted to be a medievalist, and then I found that I wasn’t well suited to it. I started to get interested in how modern thinkers have reflected on the medieval past. That led to me to right-wing radicals and how they took on medieval-inspired ideas coming from Romanticism. That was how I then became introduced to certain figures who also had larger ideas about this group identity that extended beyond Britain and that included parts of Europe, if not all of it.

What kinds of figures?

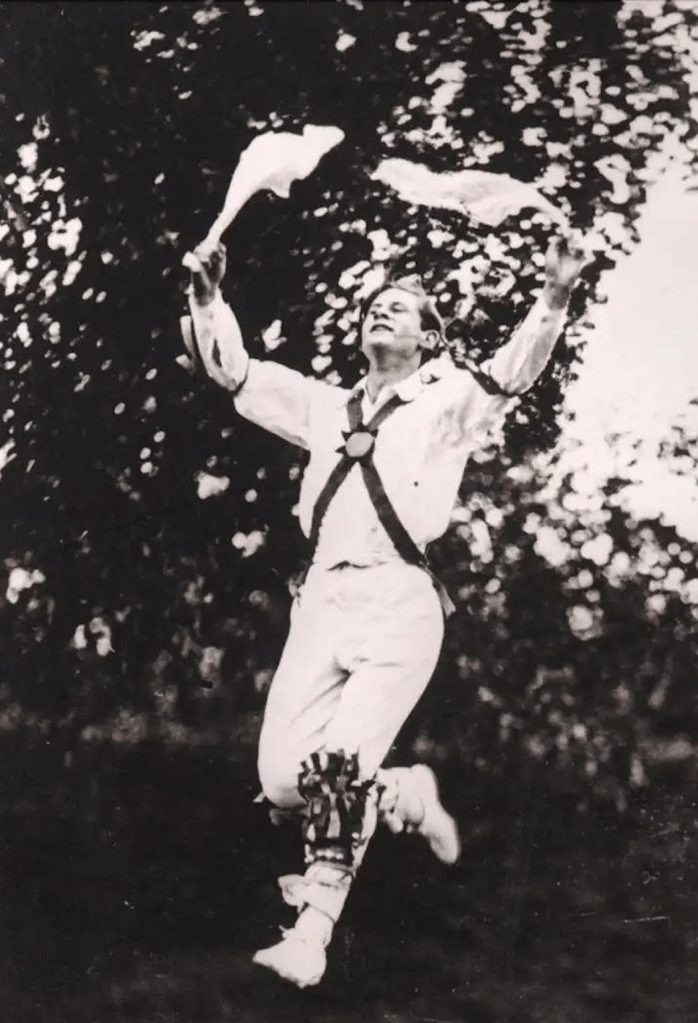

Rural figures are some of them. Two immediately come to mind: Rolf Gardiner (1902–71) and Viscount Lymington (1898–1984). They’re associated with the interwar organic movement and they went on to also influence the foundation of the Soil Association (est. 1946) as well. These might seem quite bizarre fringe figures – and to some extent they are – but they also speak to a broader European trend happening at the same time, which is looking to the deep medieval past and is seeing how that maps onto the present. And it’s starting to acknowledge that the destiny of the United Kingdom perhaps doesn’t lie in its empire and its colonies, as so many liberal figures tend to think, but actually it’s bound together with, say, Germans and the Nordic people. And, again, this ties into conceptions of racial identity, and broader cultural identities as well.

How do you differentiate between the cultural and the political aspects of your research?

The simple answer is that they’re interlinked. That’s one of the problems I have when it comes to identifying myself as an historian. Because I sort of fit uncomfortably between political history, or even diplomatic history, and what we might call intellectual history – although I prefer the roomier term ‘history of ideas’, precisely because I see culture and politics as interlinked and it allows me to look at literary sources, art sources, whatever. So the answer is that I don’t think you can particularly separate the two.

I’m conscious that what you are researching could be construed as a particularly inflammatory topic. What kinds of responses have you elicited in undertaking the research that you have?

I was once asked by an academic whether I was concerned that what I was writing could be a ‘useful’ history for modern people on the right. The answer is that I don’t feel much of a responsibility, partly because I see my dissertation as trying to understand how Britain’s relationship with Europe is not a constantly set thing when it comes to specific ideologies. It’s not liberals who have always been the ones who have imagined a future of a united Europe, as we now commonly think. In the wake of the Brexit referendum, we’ve all sat there with this clear idea about who is in favour of a united Europe and who isn’t. The past is far more muddled on that, and I think if we look at European politics today we’re starting to see this idea that the European Union or a European union might become more reactionary or right wing in the future, even if Britain is outside of it. Now, if that’s the case, then I think it’s worth considering what the British past has to say on that matter, and where our different schools of thought align. Will British conservatives, for example, change their tune on Europe – when Europe starts to become more reactionary, say, if the policy of a ‘Fortress Europe’ comes into existence – or will they maintain their anti-European stance? I don’t see this as being something that right wing people will look at and think ‘this is brilliant; this provides a blueprint of a possible future’, but I think it’s necessary to muddy the picture a little bit.

Could you give us a sense of the archives that you’re engaging with, but also if there are any whose contents have surprised you?

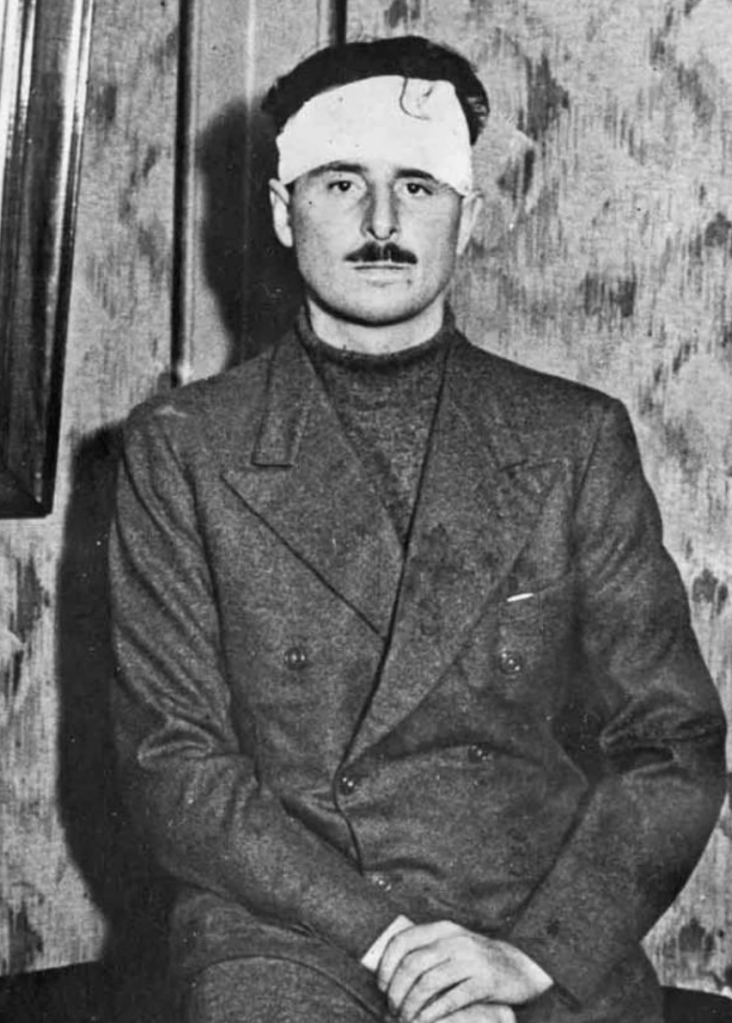

A lot of the archive research has been done before by other historians. The history of European integration is one that is well-worked by now. What I think lends my project its originality is the connections between different people on the right. Looking at Oswald Mosley’s (1896–1980) idea of a united Europe, his ‘Europe a Nation’, goes far beyond the sort of federal ideas that you’re seeing among liberal conservatives in the post-war period, even though we commonly associate those people with being the ones who are most pro-European against perhaps more Eurosceptic Labour figures, or more imperial-minded conservatives.

Mosley stands out as advocating for a vision of Europe that is about race and culture, as well as politics and economics. That goes far beyond what people like Harold Macmillan (1894–1986) or Winston Churchill (1874–1965) are talking about. But if you look at them over the course of their career – and, again, this might be a controversial thing to claim – you can find strange similarities between someone like Mosley on the one hand and Macmillan on the other. That’s something the archive research has actually helped with, is finding out, in the interwar period, how much of a radical Macmillan was taken to be by his conservative colleagues, and that this never really goes away. The Conservative Party shifts and changes over the decades, but Macmillan’s radicalism is always there beneath the surface. You start to see that, even though Mosley and Macmillan differ temperamentally, they share many ideas in common, and I believe that part of their belief in a future European project, even if they differed in degree, comes from that same radical place.

What historians guide your practice?

Well they can come from diverse places really. The historians I admire most – not to offend those who come from my own field – are those who are doing something slightly different. The one who I admire at least for his prose, is Simon Schama. His book Landscape and Memory (1995) was formative in my training. The other two that stand out for me – one who isn’t really an historian, but comes more from English, and the other who is an historian but is more of a literary figure – are John Carey and Svetlana Alexievich, the Belarussian writer. I think they give a completely different flavour to history than what most people are used to seeing.

Carey, on the one hand, takes these interwar intellectuals – cultural figures, writers, people like Virginia Woolf or D. H. Lawrence, people we’re very familiar with – and brings out the dark side of their thinking, connecting it with events of the Nazi Holocaust, which may seem completely absurd to somebody who was never read the book The Intellectuals and the Masses (1992), his work. But, reading it, it’s this fascinating exploration of how, in the interwar years, this seedbed of radical racial ideas was laid, that may have borne fruit in Germany, and didn’t in Britain, but it was there nevertheless – something that we’re keen to forget. Alexievich, on the other hand, takes these wonderful pieces of oral history and transforms them into what you might read as a fictional piece of work. But it gives much more weight to the voices of individual people from these times. Chernobyl Prayer (1997), I thought was absolutely brilliant for that. It really gave you an impression of what people were feeling and going through that wasn’t diluted by distant analysis. It gave a picture of the broader events that led up to the event, but it really put you in their shoes as well.

A concern for craft is really coming through in what you’re saying here. To what degree do you think about the craft of history, the doing of history, and the tools of the historian?

I’ve always liked what Martin Amis has to say about the novel on this, and I think it can be somewhat applicable, even in a limited way, to History. His saying is: style is morality. I think in History we’ve often tried to separate the stylistic and the analytical, when in fact the two are complementary. There are many ways to interpret what Amis means, but I think the one that I would probably draw attention to is this issue of clichéd thinking. When students or historians add a stylistic flourish to an essay, it often comes through like a vagueish cliché. Whereas, I think where Amis is right is that being careful with the language you use – and this requires great effort and literary skill as well, which is something that I’m not claiming that I have, but that I admire – is to rethink the words you’re using in such a way that it gives a completely different flavour to the ideas that you’re articulating.

Who are some novelists that you like, apart from those you’ve mentioned?

Thomas Hardy is probably the one I like most, particularly his novel Jude the Obscure (1895). That I read when I was studying for a year abroad in Berlin, and it had a massive effect on me, not least because one of the great themes of the book is this idea that Jude is an aspiring intellectual, somebody who works studiously, wants to gain a place at Christminster – Oxford – but never manages it, and is dismissed on class background. I think when I read that at the time, filled with academic anxiety, that really struck a chord with me, even though the novel is well over a century old. I’ve got a local connection with this world, being from Dorset, as well, so the places are very familiar to me. It gives it this peculiar fictional twist, so far as the places are real but the names are changed.

I want to come back to your work – are there any problems that you’ve faced in conducting research; in writing, thinking, and producing work?

I mean there are problems, of course – there always are, it’s inevitable. I find they tend to resolve themselves fairly quickly – which might be me being positive – but these problems come in major and minor forms, right? You always, as you’re doing research, have different questions come up in your head as you keep reading different material, and you start thinking this could potentially be a big problem for the dissertation. But then you have to also know your limits. You can be tugged in so many different directions when you’re reading a diverse amount of material. You can’t simply put it all in your PhD. You need to have an idea of what your limits are, what your core focus is, and if something is beneficial to that then that’s great, but just because it ties in it doesn’t necessarily mean it has to reshape the entirety of your argument.

That’s a periodic crisis that I have. Because even though those words that I’ve given you now may lend some sort of finality to this, like I’m now beyond this problem, it’s a reoccurring thing that keeps coming up. You’ll pick up a book that’s long been on the reading list, but you just haven’t quite got around to yet – and you read something and go ‘my word, this is going to completely change that entire chapter’s direction.’ But then you kind of have to sit there and go ‘well, actually, perhaps it hasn’t; perhaps the structure that I’ve delineated from reading these twenty books before hasn’t been completely changed by this one work. It’s giving me a slightly different way of thinking about it, but it hasn’t completely changed it.’

Have you had any really quite memorable moments in the archive?

From my conversations with people, memorable moments in the archives – unless you really discover some absolute gold dust, which you know might be unlikely – tend to come more from people who are dealing with older material. And there’s something about looking at older material that people can be more Romantic about. Particularly if it’s art, or it’s a map or something like that. It brings alive this childlike fascination with History, that doesn’t come when you’re sort of pouring over memoranda and minutes of meetings. It’s hard to be Romantic about that. I find the most enlightening parts come from when I process the archive research, and it comes under the glow of my lamp on my desk; when I’m sitting there and I’m making the connections between what I found in this archive and what I found in three others. And it’s when you find those connections, that’s when the project starts to come to life, and when I can start getting excited about it.

What do you think postgraduate students studying history should be aware of?

I think it needs to be made much clearer to graduate students, particularly if they have any ambition of pursuing an academic career, that there are three core parts to it, alongside a couple of minor others: one, the dissertation; two, teaching experience; and three, publication history. If that was made far clearer from the start, when you’re putting an application forward, I think a lot of people would rethink how they’re going to structure their PhD, rather than having this gradual crisis that dawns when people realise that they’re halfway through their second year and they’ve got no publication history or they haven’t given as many talks or have only just started teaching, and it just contributes to this terrible atmosphere of anxiety that you see not only within yourself but in other PhD students as well.

The other thing I would add to it is that I think PhD students need to need to chill out a little bit. We all like to have a moan about how incredibly stressed we are, but I think sometimes taking a break from it – and this is again to tie it back into novels – for every sort of five academic history pieces you read, if you desire to put aside the time to pick up a novel – it doesn’t have to be Middlemarch; it can be something like Persuasion, which is only 150 pages or so – completely refreshes your mind, gives you some new energy, and also, perhaps, if you’re fortunate enough, will give you the time to think and process, and come back and approach the way you’re writing in a slightly different way, that may make it more interesting and enjoyable for you and the person reading it.

It’s sometimes said that one’s historical research is, in a certain way, autobiographical. I wonder how far you think your research fits into that description?

What is it, Aristotle says we’re all ‘political animals’, right? Well I’ve always felt that I’m a very political animal. But not in a partisan sense – in a much more general sense, in that I’m constantly thinking about things that could be changed, things that could be improved, how these things are going to come about, what the future could look like in 100 years’ time.

It’s hard not to see a part of yourself sometimes in this. The historians of fascism, George Mosse and Roger Griffin, have this thing they call ‘methodological empathy’, which to somebody who is not well acquainted with it might sound like a quite frightening idea, particularly if you’re looking at something like fascists, because it might imply that you’re trying to sympathise with them. In reality it just means that you try and see them how they saw themselves. The practise of doing that is a fascinating one, because you discover that a lot of these people, even if they have ideas that are completely different to yours or other people you’re looking at, can come from similar places, and that’s how you can make connections between them and yourself. So, if you have a Romantic influence yourself and you can sense it in Nazism, then that makes a far more disturbing picture and completely changes the way that you see National Socialism than if you hadn’t made that connection at all. So, it’s not about seeing myself in any of these people, it’s more about reckoning with the fact that when you’re trying to imagine a future it’s often interesting to look back and see how others imagined it in the past as well, and how these things can differ in various ways but also how they can be remarkably similar in others.