By Tiéphaine Thomason, @teaphaine

It should come as no surprise that, in a society of highly variable literacy, satire was often oral. Such was the world of the Parisian street in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This satire was often set to popular tunes to be sung, as well as recited, and stuck up on posters that would have been read aloud by passers-by for their less literate peers.[1]

Much maligned throughout history, the Jesuits naturally made an appearance in this oral satire of Parisian streets. Thought to have the ear of the king as confessors, reputed to be morally lax, and mistrusted through their ties to a non-francophone world, the Jesuits were despised. The polemics in which the Jesuits were embroiled, and which made their way into street satire, ranged from disputes regarding their missionary practices outside of Europe, their changing theological positions on sin, and even the odd witch trial.[2]

The Jesuits were often described in devilish terms in satirical material. However, alongside mentions of demons and serpents, there was a persistent reference to ‘turkeys.’ In French this is ‘[des] dindons,’ or, more specifically, Jesuits as ‘[les] dindons d’Ignace,’ that is, ‘turkeys of Ignatius,’ referring to Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order.

But why turkeys? If this portrait of the Jesuits is odd to modern eyes, these Jesuit ‘turkeys’ perhaps best encapsulate the key criticisms of the order in the period. For instance, the Jesuit ‘turkeys’ are described in satire as preaching their casuistic views to a Parisian flock. Much like the gobbles or cries of the turkey, the theological arguments of the Jesuits are depicted as foolish and nonsensical. Crucially, according to Alexandre Dumas’s much later Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine (1873), the turkey was a bird introduced to France by the Jesuits from North America.[3] The name ‘dindon’ or ‘dinde’ derives from ‘d’Inde’ – meaning ‘of India’ – with this ‘India’ referring to the Americas. Here, a nod to turkeys in satire was a constant reminder that the Jesuits had, to the early eighteenth-century Parisian mind, a ‘foreignness’ about them. Finally, the word ‘dindon’ rhymed with a range of jovial popular tunes and their (often nonsense) refrains – such as the nonsense word ‘faridondon.’ And after all, it’s rather hard to resist a good rhyme.

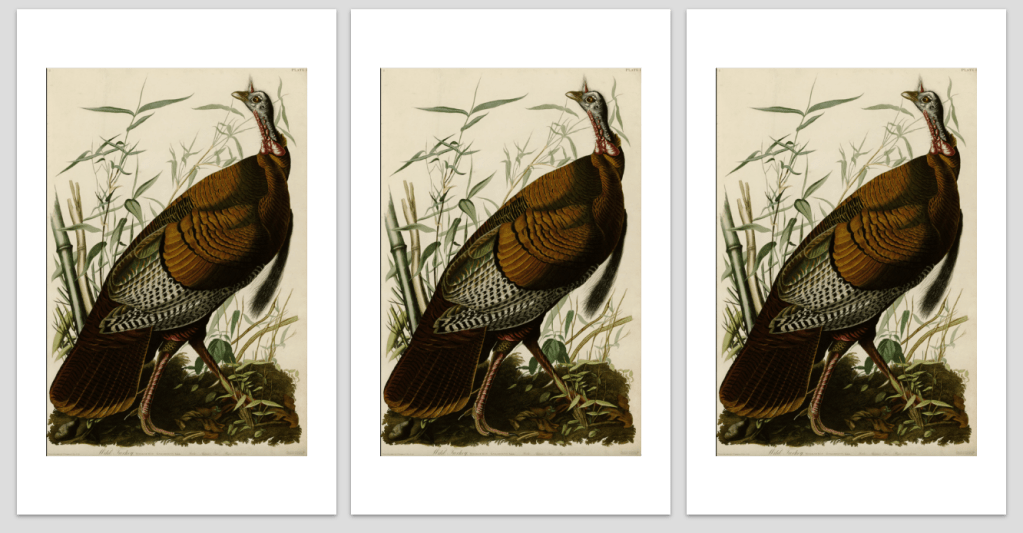

Cover image: Plate 1 of Birds of America by John James Audubon depicting Wild Turkey. Engraved from painting made by John James Audubon, 1825.

[1] On public reading and reading aloud, see Roger Chartier, ‘Loisir et sociabilité : lire à haute voix dans l’Europe moderne,’ Littératures classiques, 12, 1990, 127-147 ; Henri Jean Martin has also touched upon this in Histoire et pouvoirs de l’écrit (Paris : A. Michel, 1996).

[2] See, for instance, the Chinese Rites controversy, Yu Liu, ‘Behind the Façade of the Rites Controversy: The Intriguing Contrast of Chinese and European Theism,’ Journal of Religious History, vol. 44, no. 1 (2020), pp. 3–26; and Jean-Pascal Gay, ‘Le jésuite improbable : remarques sur la mise en place du mythe du Jésuite corrupteur de la morale en France à l’époque moderne’ in eds. Pierre-Antoine Fabre and Catherine Maire, Les antijésuites: Discours, figures et lieux de l’antijésuitisme à l’époque moderne, Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2010.

[3] Alexandre Dumas, Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine, Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1873.