By Dr. Stephanie Brown (Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/stephemmabrown.bsky.social)

Old Bailey Online is a vast and searchable digital collection of nearly 200,000 trial accounts from London’s central criminal court from 1674 to 1913.1 A pioneer of digital humanities, Old Bailey Online also holds remarkable pedagogical value. In my teaching, I have found it to be an unparalleled resource for introducing students to the complexities of crime, justice, and society. This article reflects on my use of Old Bailey Online in undergraduate and postgraduate seminars and workshops. It is for anyone new to teaching or for experienced lecturers wanting to teach with digital archives.

The first pedagogical hurdle is often orientation. For students new to digital archives, the sheer volume of material at Old Bailey Online can be overwhelming. The best place to start, for researcher and student alike, is the project guide on reading Old Bailey trials.2 Whether this is guided learning, or preparation work assigned before class, this guide provides a blueprint for navigating a trial record – from the defendant, to the indictment, to witnesses, to the verdict.

Following this, to help undergraduates gain confidence, it is best to begin with carefully framed exploratory tasks. We might, for instance, search for “theft” trials between 1800 and 1820, then filter by gender, age, or verdict. This exercise assists students in becoming familiar with the database and allows them to begin discussing their findings.

For Kara Kennedy, the use of digital archives in humanities classrooms is ‘an ethical duty and a feminist imperative’ bringing technical experience to students less likely to have been exposed to these skills.3 This is hugely important, but the pedagogical benefits of using Old Bailey Online go far beyond the technical. Using digital archives allows students to discover for themselves the problematic nature of historical knowledge; how it is shaped by questions asked, methods applied, and the silences in the source material.

The ease of searching can give the illusion of simple answers. However, meaningful engagement requires critical reading and contextual knowledge. One of the most important lessons is that these are not verbatim records. Trial reports in Old Bailey Online are derived from published accounts, produced for print and were often edited for clarity, morality, or entertainment. They were shaped by shorthand writers, court clerks, and editors, and must be read with attention to their framing and omissions.4

By adopting a critical lens, students move from surface reading to a deeper understanding of the archive as constructed texts shaped by cultural and institutional dynamics. Students begin to see the courtroom not only as a site of law, but as a space where status, identity, and credibility were continuously negotiated.

In one undergraduate workshop, we compared trials involving infanticide and theft, exploring how women were portrayed in relation to motherhood, domesticity, and criminality. They quickly noticed how female defendants were narrated through moral judgement, some described in vivid detail as deviant or unnatural mothers, while others were dismissed in a few perfunctory lines. This exercise prompted discussion about the social expectations placed on women and the legal language used to reinforce or subvert these roles. They were encouraged to situate their findings within the historiography on women and crime, grappling with how historical narratives are constructed, challenged, and reinterpreted.5

Old Bailey Online is not limited to teaching crime or legal history. It can be a powerful tool for uncovering the textures of everyday life in early modern and Victorian London. In another session, students explored witness statements as a source of social history, identifying the voices and experiences of people often marginalised in traditional archives. For example, Adam Crymble and Emma Azid built a database of nearly 700 references to people of Black or possibly Black African heritage in the trial records between 1720 and 1841.6 Their work demonstrates how the archive can be re-read through new questions, not necessarily to trace crime and punishment, but to reconstruct the lives and communities of Black Londoners. Inspired by this approach, we examined language in the courtroom and considered how power, identity, and marginalisation played out through the formal processes of trial reporting.

These examples do more than illustrate historical content, they help demystify the process of historical research itself. Each time undergraduates interrogate a trial record, frame a new question, or compare cases across time or theme, they engage in the interpretive practice that defines historical inquiry. Rather than passively absorbing information, they become active participants in the production of knowledge. Through Old Bailey Online, they encounter the courtroom not only as a site of justice but as a stage on which stories were told, identities constructed, and social norms contested. The archive thus becomes both a record and a provocation: a space for critical reading, creative questioning, and collaborative discovery.

About the Author:

Dr Stephanie Brown is Lecturer in Criminology at the University of Hull and member of the Cultures of Incarceration Centre. She is a historical criminologist researching crime, punishment, and policing from the middle ages to the modern-day. Her expertise is in the history, context, and law of homicide, suicide, and abortion. Stephanie is interested in critical and archival pedagogies and has extensive experience using digital resources such as Old Bailey Online and Medieval Murder Maps in Higher Education. She completed her PhD at Cambridge’s Faculty of History and CAMPOP. She held postdoctoral fellowships at the Cambridge Institute of Criminology and the Institute of Historical Research.

References:

- Hitchcock, T., Shoemaker, R., Emsley, C., Howard, S., and McLaughlin, J., et al., The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674-1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0, June 2025). ↩︎

- Ibid, ‘How to Read an Old Bailey Trial’ https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/about/howtoreadtrial (June, 2025) ↩︎

- Kennedy, K. ‘A long-belated welcome: accepting digital humanities methods into non-DH classrooms’, Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11.3 (2017) 1-25. ↩︎

- Shoemaker, R. B., ‘The Old Bailey Proceedings and the Representation of Crime and Criminal Justice in Eighteenth-Century London’, Journal of British Studies 47 (2008) 559–580; Hitchcock, T. and Turkel, W.J., ‘The Old Bailey proceedings, 1674–1913: text mining for evidence of court behavior’, Law and History Review, 34.4 (2016) 929-955. ↩︎

- See Brown, S. E. “No Explanation Needed: Gendered Narratives of Violent Crime”, Banwel, S., Black, L., Cecil, D.K., Djamba, Y.K., Kimuna, S.R., Milne, E., Seal, L., and Tenkorang, E.Y. eds. The Emerald International Handbook of Feminist Perspectives on Women’s Acts of Violence, (Leeds, 2023), pp. 19-32; D’Cruze, S. and Jackson, L., Women, Crime and Justice in England since 1600 (Basingstoke, 2009); Kilday, A., Women and violent crime in enlightenment Scotland (Woodbridge, 2015); McKay, L., ‘Why they stole: Women in the Old Bailey, 1779-1789’, Journal of Social History, 32 (1999), 623-39; Seal, L., Women, murder and femininity: Gender representations of women who kill (Basingstoke, 2010); Walker, G., Crime, gender and social order in early modern England (Cambridge, 2003); Wilczynski, A., ‘Images of women who kill their infants’, Women & Criminal Justice, 2.2 (1991) 71-88. ↩︎

- Crymble, A. and Azid, E. ‘Black Lives, British Justice: Black People in London Criminal Justice Records, 1720-1841’, Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation, 2.2 (2021) 1-11; and Crymble, A., & Azid, E. Black Lives, British Justice: Black people in London Criminal Justice Records 1720-1841 (1.0) (2021). [Data set]. ↩︎

Image Credits:

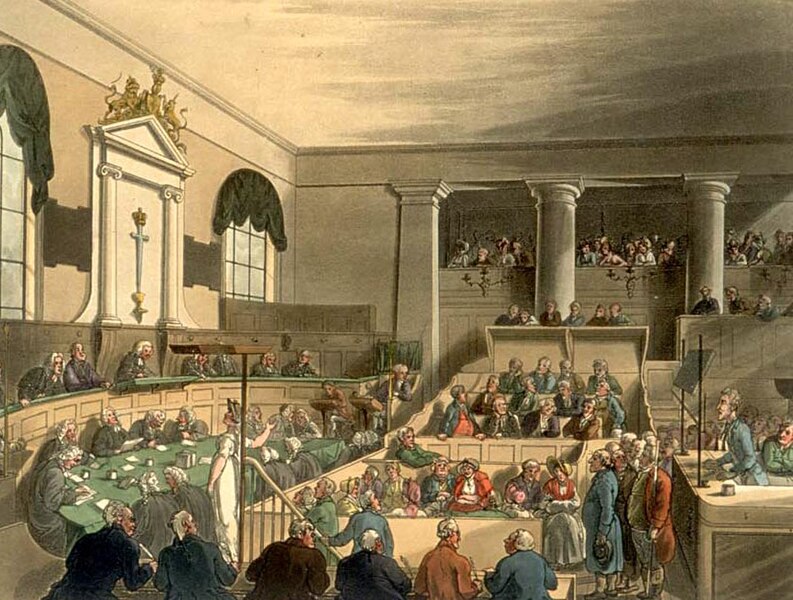

Cover image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Bailey#/media/File:Microcosm_of_London_Plate_058_-_Old_Bailey_edited.jpg

Profile picture: Shot by Chris Lacey Potography