Alex White (@alex_j_white), interviewed by Zara Kesterton

Historian Highlight is an ongoing series sharing the research experiences of historians in the History Faculty in Cambridge. We ask students how they came to research their topic, their favourite archival find, as well as the best (and worst) advice they’ve received as academics in training. History is all about how we tell stories – and this series looks at the stories we have to tell as postgraduate students. In our latest post, the former editor-in-chief of Doing History in Public Alex White tells us about his work on anti-colonial radio broadcasting in East Africa.

What are you currently researching?

I submitted my thesis for examination in April, so I’m currently in the final stages of my PhD! My research focuses on anti-colonial radio broadcasting in British East Africa, looking at everything from the activists who created programmes to the influence of ‘subversive’ broadcasts in colonial territories. I’m particularly interested in the lives of the various listeners to anti-colonial radio and how they formed themselves into audiences. Radio has a transnational quality, and international broadcasts offered East Africans a rare form of participation in the global politics of anti-colonial activism. However, I point out it also attracted the attention of a hostile ‘counter-audience’ of radio monitors and colonial officials. Fearing mass insurrection, administrators began to pour money into costly counterpropaganda services, suppressing East African audiences with radio bans and political arrests. During the Suez Crisis, the Royal Air Force even bombed the main transmitters of the Egyptian international service in the hopes that it might prevent Arab and African listeners from hearing Radio Cairo. If you want to understand the effects of anti-colonial broadcasting, I argue that you ultimately have to examine their influence over the policies of nervous colonial states.[1]

What led you to research this topic?

It’s a long story! I’ve always been interested in how people organise themselves into new political communities. In another life, I think I could have ended up getting obsessed by some obscure faction in the Russian Revolution or the art of governance in medieval Turkey. As an undergrad at the University of Edinburgh, however, I started taking classes with Emma Hunter. Her work introduced me to the complex political world of late colonial East Africa – a period which was dominated by debates about how society should be organised and about what form governments should take after the end of colonial rule. African decolonisation is sometimes seen in a kind of pessimistic hindsight, but I think that approach risks ignoring the radical ambitions of anti-colonial activists and their complex ideas about how to build a more equal world. In this sense, listening to anti-colonial radio broadcasts was a way of participating in a vibrant international conversation. Being an audience member was a political act, whether you agreed with the ideas of the broadcasts or rejected them completely.

What’s the most interesting historical material you’ve read, listened to, or watched in the last month?

I’m currently visiting my partner in Kampala, and it’s been particularly special to visit the Uganda Museum and Uganda National Mosque – two sites which tell two very different versions of the region’s history. The Museum promotes a nationalist vision of Uganda, combining all its ethnic and religious traditions into a cohesive whole. In the grounds, there are examples of traditional buildings from each of Uganda’s regions, arranged as if they were in a single village (fig. 1). It reminds me of Victoria Gorham’s work on ‘village museums’ in Kenya and Tanzania, in which the museum becomes a symbol and a stand-in for the nation itself.[2] By contrast, the National Mosque is more about Uganda’s global connections. The modern building was commissioned by Muammar al-Gaddafi in the 2000s as a goodwill gesture – and a chance to build the dictator’s international reputation. Inside, the design intentionally mixes materials from around the world – Egyptian chandeliers, Turkish carpets, Italian stained glass and wood from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (fig. 2). If the Museum looks inward to find the source of Uganda’s national identity, the Mosque looks outward toward a wider world whose history is interwoven with East Africa’s own.

And what’s the best or most unusual experience in an archive?

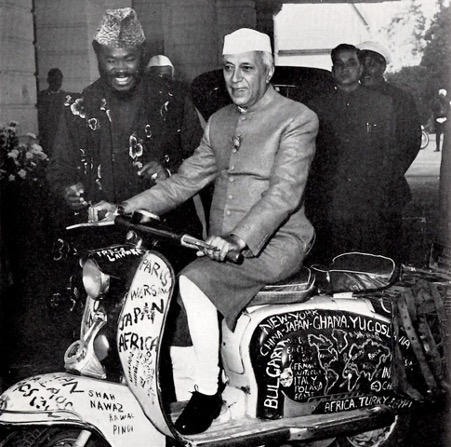

I’m always interested when a historical figure seems to be following you through the archive, turning up in unexpected places. For a while that figure was the Nigerian journalist Ọlábísí Àjàlá, who travelled most of the world by motorbike between 1952 and 1964 (fig. 3). Radio monitoring reports reveal that he worked for international broadcasters on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict, and then again on both sides of the Papua conflict in Southeast Asia. He turns up in Soviet and Indian newspapers, too – usually making friends with African students and talking about the power of Afro-Asian solidarity. He acted in a Robert Mitchum film in 1953 and made a name for himself on an Italian gameshow in 1955. There are even two popular songs about him in Nigeria – one about how he loved to travel and one, revealingly, about how he never paid his debts. I think historians sometimes focus too much on ‘transnational lives’ at the expense of everyday immobility. However, Àjàlá’s experiences speak to the extraordinary interest in travel and Afro-Asian solidarity across the late colonial world.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever been given as a historian?

Be flexible! I owe my supervisor, Ruth Watson, for this one. I started my PhD in 2019 with a very rigid idea of what I was going to research and what I was going to find. Five months later, we were living in lockdown and all of the countries I wanted to visit were suddenly off-limits. Like so many students, I was faced with the choice of radically changing what I studied or putting off research for months, even years, until travel was possible again. Ruth suggested that I change my thesis to focus more on British sources and examine how the British interpreted and responded to broadcasts. I wasn’t enthusiastic at first, but it ended up being an important part of my thesis and a really engaging subject. This advice might be specific to people who started work during a pandemic, but I think it’s useful in any situation. You never know where your research is going to lead before it begins, and you never know how good an archive is going to be until you’re tried it. Moving past your first impressions to follow unexpected leads is a really important part of the research process and can help produce more accurate, accessible and interesting writing.

And the worst?

I’m always a little annoyed when people argue that academia is the only thing you can do with a PhD in History. With the academic job market in its current state, and funding for humanities departments dwindling every year, that kind of thinking strikes me as a little irresponsible. Only a tiny number of researchers will have that ‘perfect’ transition from PhD to postdoc to stable academic career. The bright side is that it’s not the end of the world to follow a different path. Personally, I know so many former PhD students working in think tanks, government service, cultural institutes and the media where their expertise is really valued. Contingent Magazine is a brilliant showcase of how historical research is surviving and thriving outside the university sector. I think that postgraduates sometimes sell themselves short by assuming their skills are only useful in a traditional academic setting. The job market is always tough, but there are so many more options available if that’s the path you choose.

What’s your must-do Cambridge experience?

Definitely Sala Thong, the Thai restaurant on Newnham Road! Their red curry is delicious, they’re really accessible for vegetarians and vegans, and I still dream of their spring rolls. It’s also right opposite The Granta, so if you want to keep the night going you can settle there for a pint by the river. As far as I’m concerned, that’s Cambridge at its very best.

[1] For more on the concept of colonial ‘nerves’, see Nancy Rose Hunt, A Nervous State: Violence, Remedies, and Reverie in Colonial Congo (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016) and Marissa Moorman, Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State Power, and the Cold War in Angola, 1931–2002 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019).

[2] M. Victoria Gorham, ‘Displaying the Nation: Museums and Nation-Building in Tanzania and Kenya’, African Studies Review 63/3 (2020), 487–517.