Historian Highlight is an ongoing series sharing the research experiences of historians in the History Faculty in Cambridge and beyond. In this instalment, Chris Campbell sat down with second-year History PhD student Molly Groarke to discuss imperial history, heritage organisations, and public-facing research.

@mollygroarke | @chriscampbell

Molly, let’s start by talking about your PhD research.

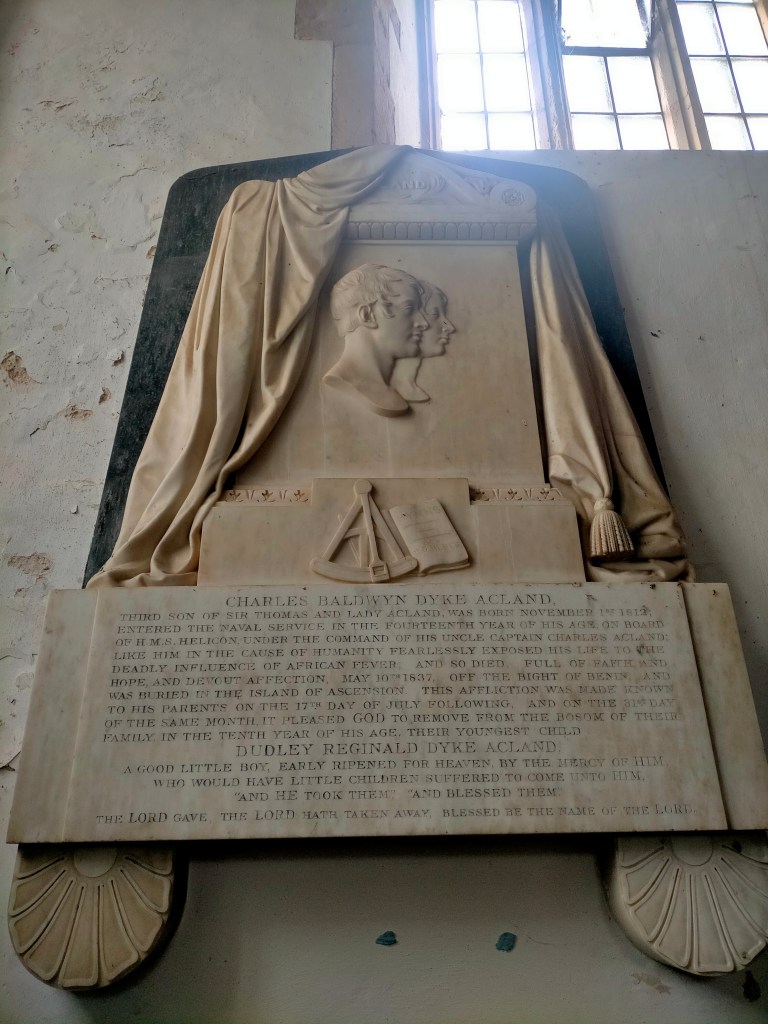

In my PhD, I’m writing a history of the British Empire in the nineteenth century, but through the lens of one particular family. The family was the Aclands of Killerton; they lived in Devon and were involved in abolitionist, evangelical, and philanthropic political circles. Their role as gentry landowners and local community leaders has been researched, but there’s not been much written on what they were doing globally; I think their local, elite, political identity was very important to their commitment to imperial service. I’m especially exploring their antislavery ideas, their involvement with the Royal Navy and the army, and their support of missionary societies and overseas charitable work.

Did you come to this topic fresh or has it been influenced by previous research?

I actually didn’t design this project – I’m hosted by the National Trust who proposed that someone should do research into the Acland family and their global links, and I applied to do it. The Trust now look after Killerton House, which is where the Acland family used to live. I could have taken the project in multiple directions, but I chose to focus on the ideas of imperial service, family identity, and antislavery. That was influenced by some work I did during my master’s at St Andrews, looking at British abolitionism. For my undergrad and master’s dissertations, though, I was looking at anticolonial ideas in the twentieth century, so I have made a bit of a leap since then.

So, you’re working in conjunction with a public-facing organisation – has this shaped your approach to research in any way?

I don’t think it has affected the actual research that I do. The National Trust is what’s called an Independent Research Organisation, so while they’ve set the parameters of my project, they don’t dictate which direction I should take it in. They’ve directed me to the main sources of my research which is the Acland family archive at Devon Record Office and also the collections at Killerton House. So, I can focus on whatever I want within those collections and those parameters. I haven’t done much material culture research before, but given that there’s an entire country house full of objects at my disposal, I’ve started to steer in that direction. That’s been interesting in shaping the types of things I look at.

What is the public application of your research, then?

At Killerton House, which is now a visitor attraction, the National Trust will hopefully be able to communicate more diverse stories about the Aclands after my research has been completed. It might give visitors a more nuanced sense of the country house not just as a local centre of power, but as a global one too. Really broadly, I hope research like mine will show the importance of not letting heritage sites be static monuments but places in need of continual reinterpretation.

Is there anything that’s emerged in your research that’s challenged views you previously held?

I think before my PhD, I understood the British Empire to be a kind of profit-making exercise, both in terms of financial profits but also profits in the sense of social and cultural prestige. The Aclands didn’t profit economically from empire, but they did use colonial enterprise and the antislavery movement to gain significant influence at home and abroad, through employment, political groups, and social connections. Previously I thought justificatory language about the moral rightness of empire was a rhetorical device, and elites were knowingly obscuring more selfish motives. But the Aclands really did have a genuine belief in the benefits of the British Empire for the rest of the world; they had this language of self-sacrifice, even privately amongst themselves, that keeps recurring when they were not gaining anything from it personally. So, I think through studying the Aclands I’ve found that there could be a much deeper ideological conviction in imperialism than I’d previously thought – they weren’t just co-opting that language for their own purpose.

You touch on topics that come up frequently in public debates about history – does this make researching in this area difficult?

I don’t think it makes the research difficult, but it does make any aspect of communicating it potentially sensitive. If I were to write a blog post or an article that might have a public facing audience, I have to be careful about the words I use. That isn’t to say that I shy away from the obvious implications of my research, but recognise that some terms can have loaded meanings to different audiences, particularly given the prevalence of British Empire history in the ‘culture wars’ debates. Although I would say, about the culture wars, while on one hand it stifles genuine historical debate in the public sphere because one side of that debate refuse to recognise the atrocities of empire, on the other it has brought home to a much wider section of the public the importance of history to present day society, so it’s not all been bad.

On that, then, and thinking a bit more about those publicly-contested areas of history, what do you think the role of the historian is in public life?

I think this is something where I’m still working out what I believe. There are obvious problems with some histories that are written to supply a demand, say a public demand for a particular historical narrative. If you’re writing a history of something knowing what you want to find, that can of course skew your results. However, I think a greater risk would be for the historian to have no role in public life at all, because that would mean legitimate history wouldn’t have a voice. I also think that I chose to study history when I first went to university because I had a belief in its importance in public life. If you stop historians having a public role because it might damage the quality of the research, then you lose all those historians who chose the profession because of its public and political importance; you make history a much less diverse profession, which would have a worse consequence for the quality of research.

Do you draw any distinction between academically-trained historians and other professionals who work in history, in the heritage or museum sectors for example? Is it even worth making such distinctions?

Obviously really high quality research goes on both inside and out of academia. I suppose that in heritage you do tend to get more of the demand-driven history that I was talking about, but I don’t think we’re by any means insulated from that in academia. In that sense, I guess there’s no need to draw too much of a distinction – we’re all ultimately working towards the same goal of investigating and communicating history.

Can you tell me about some of the historians you admire, and who particularly inform your thinking?

In the historiography of families and the British Empire, I particularly like Margot Finn, Katie Donnington, Catherine Hall, and Adele Perry. More broadly, some historians of colonialism that I admire are Jane Sampson, Alan Lester, and Zoe Laidlaw.

What’s been your best experience during the PhD?

I’ve liked having supervisions as a PhD student; it’s been really interesting to talk to my supervisor and advisor at a really in-depth level during this project, and get so much personalised feedback. My supervisor has been really supportive so I’ve been lucky in that sense. I would also say – and this surprised me, because I previously didn’t like public speaking – but I’ve quite liked presenting my research, whether that’s to audiences in college, at some of Cambridge’s graduate workshops, or to National Trust staff and volunteers.

A history PhD can be immensely rewarding in itself, but obviously comes with its own unique challenges. So, for the final question, what advice would you give to someone just beginning theirs?

PhD progress can be quite erratic (or at least mine is!), so I think good advice would be not to compare yourself to others in your cohort. Everyone’s archive trips are different, everyone wants to spend time doing extra-curricular stuff at different stages, so different PhDs have different schedules. I’d also say enjoy taking the time to read in your first year, and don’t stress out about not having achieved much in terms of writing. Also, get Notion to take notes and write out plans – I’m not sponsored but it’s very good!