by Tiéphaine Thomason (@teaphaine)

It’s a soggy, grey October. The boiler’s acting up, you’re stuck at home in a jumper, wishing you were elsewhere. At times like this, it seems natural to gravitate towards tales of warmer places.

Out of the corner of my eye I can see Tim Cope’s ‘On the Trail of Genghis Khan.’[1] As the title indicates, Cope recreated a 10,000 km journey from Mongolia to Hungary. Making his way across the steppe and meeting those that lived within it, he travelled a route that no westerner had completed before. By commenting on forbidding landscapes and distant cultures, travel writing seems to offer endless pleasures. Those of you looking for a slightly more classic version of this genre – this is usually code for European and loosely 19th century – might try Stendhal’s ‘Promenades dans Rome’ or Dickens’s more creatively named ‘Pictures from Italy.’[2] The travelogue is, of course, by no means a new genre – perhaps one of its best examples is Ibn Battutah’s 14th century ‘Rihla’ – nor should the genre be seen as particularly European.[3]

With that said, it is also a historical source used by historians and literary scholars from European academic traditions. This is for several reasons – not least that travelogues rather neatly compile material on various cultures and geographies in a way that cannot be easily found in other sources. As outsiders from the present looking back to the past, we benefit, as readers, from the perspective of a geographic or cultural outsider – the travel writer. In an ideal world, these would comment on those traditions and mannerisms that distinguish one group from another. They might also point out unexpected similarities between different communities. In the 1720s, the Jesuit priest Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix noted in his travels to Québec that those born in the city of Québec spoke with the same accent as Parisians back in metropolitan France.[4] This small detail should be humbling to those of us with metropolitan French accents who have, at times, struggled in conversation with our Québecois friends.

The lack of sources on a particular culture, which usually prompts historians’ use of travel narratives, can be due to poor record keeping or a lack of interest in certain cultural foibles. (Why should the 18th century law courts of Québec comment on the accent of their speakers?) Crucially however, a loss of (balanced) source material can also often be due to violence inflicted upon a culture by a foreign party. This is overwhelmingly the case for those non-European cultures discussed in European travelogues on the Americas and Africa from the early modern period onwards. The writer almost always belongs to the party of the colonising power. In many cases, the following question presents itself. How do you read a source where the travel writer has inherited, created, partaken in, and disseminated hateful – and often violent – views on those who they are ‘encountering’? Even where these views are not at the forefront of the narrative, it can be hard to get away from the biases that permeate every page.

A good example of this is Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane (1758).[5] It centres on his time living with the Natchez people from 1720 to 1726, after which he became the manager of the plantation of the Compagnie des Indes in New Orleans. Perhaps one of the most referenced travelogues in the historiography of early eighteenth-century Louisiana, Le Page devotes pages to the intricacies of Natchez culture and language. Having learnt the Natchez language, he relates Natchez vocabulary and customs to his metropolitan readers. He discusses conventions in conversation and outlines social complexities within the community. He notes, for instance, the presence of both a genderlect and a sociolect among the Natchez.

Yet, Le Page was also present during – and likely complicit in – the massacre of the Natchez in 1731 by the French. The aim was to wipe out the Natchez people – genocide – and those who weren’t killed were rounded up and trafficked as slaves to the island of Saint-Domingue. The few who did escape sought refuge among the Chickasaw, before being even further dispersed. The Natchez language, so keenly related by Le Page, has since disappeared.

When writing about his years among the Natchez, Le Page was doing so with full knowledge of what would happen to them only a few years later. Yet his account of the massacre is at best apathetic, at worst, somewhat smug at the prospect of French ‘victory’ – so how do we read something like the Histoire de la Louisiane?

There has been plenty of work in recent years centred on ‘reading along the bias grain’ – the historian Marisa Fuentes’s suggestion for pushing the concept of ‘reading against the grain’ in the archive further. Fuentes’s work centres on free and enslaved black women in the 17th and 18th centuries and their bodies.[6] That is, looking at gaps and silences in the archive to recover those voices which are drowned out by those such as Le Page’s. However, Fuentes’s style – which builds on that of Saidiya Hartman – is difficult to pull off for those of us who haven’t been doing this sort of history for quite as long. Crucially, as Hartman points out, this work needs to be done extremely carefully. In attempting to recover lost voices in the archive, there’s always a risk of doing further violence to them.[7]

Where travelogues are concerned, a first step simply consists in being aware of what each interaction described in the text is looking to achieve for the narrator – and then seeing whether anything is left between those gaps that needs explaining. Returning to the example of Le Page’s interaction with the Natchez people, literary scholars working on indigenous voices in North America have identified several ‘tropes’ within travelogues that European writers have indigenous speakers fulfil when speaking in a narrative.[8] These thus likely denote an artificial interaction, and encompass:

- Referential speech – that is, teaching the reader about a group or landscape.

- Actantial speech – serving as ‘gesture’ in the text to point something out to the reader.

- Contestatory speech – where indigenous voices are used by the travel writer to criticise European tendencies.

- Attestative speech – typically attesting to the veracity of an event or relationship.

- Heroizing speech – which heroizes of the writer or Europeans.

These criticisms do not mean that we should completely dismiss the travelogue as a source. Rather, like any other source, travel narratives require careful reading and cautious use. Ultimately – if you want to feel like you’ve been whisked away to another land this October, you’d probably be better off reading something more recent and closer to home – maybe give Bill Bryson’s ‘Notes from a Small Island’ a try? [9]

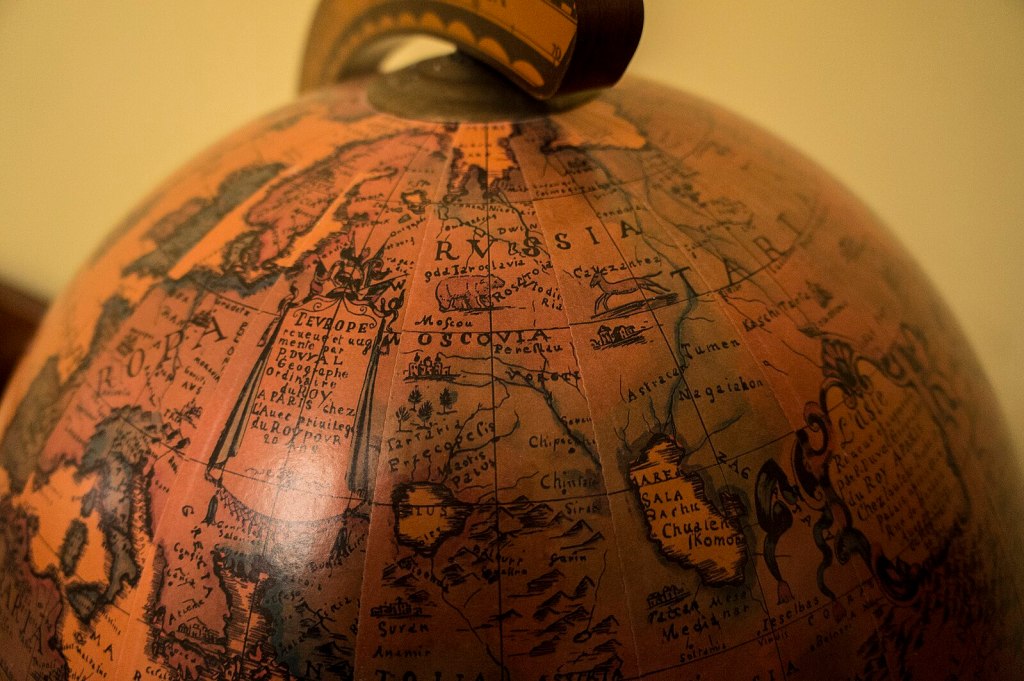

Featured image : Replica of old French globe, sight on Russia, Petar Milošević, Wikimedia Commons, 2o13.

[1] Having not finished this book yet – I can’t endorse it, but the documentary based around his experience is worth a watch and available on most streaming services. Do also note that, by virtue of the journey he undertook, Tim Cope is not wholly exempt from engaging in somewhat orientalist tendencies, Tim Cope, On the Trail of Genghis Khan: An Epic Journey through the Land of the Nomads (Bloomsbury, USA: 2015).

[2] A good edition of Stendhal’s Promenades dans Rome is the 1997 Folio edition (Gallimard). As for Dickens’s Pictures from Italy, there is a good, widely available Penguin Classics edition with an introduction by Kate Flint from 1998.

[3] An edited version can be found under The Travels of Ibn Battutah, edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith (Picador: 2002).

[4] ‘ […] nulle part ailleurs on ne parle plus purement notre Langue. On ne remarque même ici aucun Accent,’ taken as ‘[…] no where else does one speak more purely our language. One does not even notice an Accent,’ in ‘Troisième Lettre, Description de Quebec, Caractere de ses Habitans & de la façon de vivre dans la Colonie Françoise’ in Charlevoix, Journal d’un Voyage fait par ordre du Roi dans l’Amérique septentrionnale: adressé à Madame la Duchesse de Lesdiguieres, tome troisième (Paris: chez Didot, Libraire, Quai des Augustins, 1744), p. 79 ; for a discussion of these accents, see Jean-Denis Gendron, D’où vient l’accent des Québécois? Et celui des Parisiens? Essai sur l’origine des accents: contribution à l’histoire de la prononciation du français moderne (Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2007).

[5] Antoine-Simon le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane contenant la découverte de ce vaste pays; sa description géographique ; un voyage dans les terres ; l’histoire naturelle ; les moeurs, coutumes & religion des naturels, avec leurs origines, tome 3 (Paris: chez De Bure, l’Aîné, sur le quay des Augustins, 1758).

[6] Marisa Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives, Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

[7] Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts,’ Small Axe: a Journal of Criticism, 12, 2008, 1-14.

[8] The most helpful book on this for material like that of Le Page is undoubtedly by Luc Vaillancourt, Sandrine Tailleur, and Émilie Urbain (eds.), Voix autochtones dans les écrits de la Nouvelle-France (Paris: Hermann, 2019).

[9] Bill Bryson’s (American) perspective on Britain has been known to foster a new appreciation for the country, see Bill Bryson, Notes from a Small Island: Journey through Britain (Transworld Publishers, 2015).