By Floris Winckel

It’s the season of gift-giving. Some of you might be cash-strapped or lost for ideas of what to give (or indeed both). In December 1610, Johannes Kepler, imperial mathematician to the Holy Roman Emperor and one of the most renowned intellectual figures of early modern Europe, found himself in exactly this position. He sought a New Year’s gift for his patron, court counsellor Johannes Matthaeus Wacker von Wackenfels, but set himself the challenge of finding something so small and insignificant, so inexpensive and fleeting, that it approximated Nothing.[1]

Kepler considered several candidates – grains of dust, sparks of fire, wisps of smoke – none of which were suitably insignificant whilst also lending themselves to a witty reflection on their forms. Then, supposedly whilst walking along the Charles Bridge in Prague, he noticed a flurry of snowflakes landing on his coat. ‘By Hercules! Here was something smaller than a drop, yet endowed with shape’: the ideal gifts for one ‘who has Nothing, and receives Nothing’ fell from the heavens, looking like the stars that Kepler was studying and cataloguing for his day job.[2]

Kepler quickly got to work on what would become De Nive Sexangula (1611), a twenty-four-page booklet in which he playfully seeks an explanation for why the snowflake has six corners. On his journey to find the answer, he takes the reader on a whistlestop tour of other hexagonal structures found in nature, from beehives to diamonds, leaving in his wake a string of questions regarding the causes of such distinctive patterns. More problems are raised than solutions given. Ultimately, he leaves it to the chemists to explain what “formative faculty” dictates the growth of a snowflake.

In a seemingly unintentional manner, Kepler’s light-hearted exploration of the snowflake set off more than three centuries of snowflake studies, and as helped form the foundations of the field of crystallography. The booklet was reproduced in numerous editions (the latest appearing in 2014), and still inspires many a scholarly article, essay, or blog post (hello!). So, for the reader still looking for a festive gift, maybe think smaller: who knows what might come from Nothing?

[1] This is a reference to Jean Passerat’s poem De Nihilo (1582), also sent as a New Year’s Gift to his patron Henri de Mesmes, and which Wacker was an admirer of and which Kepler likely drew inspiration from. On the influence of this poem, see Paul White, ‘The Poetics of Nothing: Jean Passerat’s “De Nihilo” and its Legacy’ Erudition and the Republic of Letters 5:3 (2020), pp. 237–273.

[2] Johannes Kepler, The Six-Cornered Snowflake: A New Year’s Gift (Philadelphia, 2010), p. 33. Conveniently, the Latin word for snow (Nix) sounds almost identical in pronunciation to the German word for nothing (nichts).

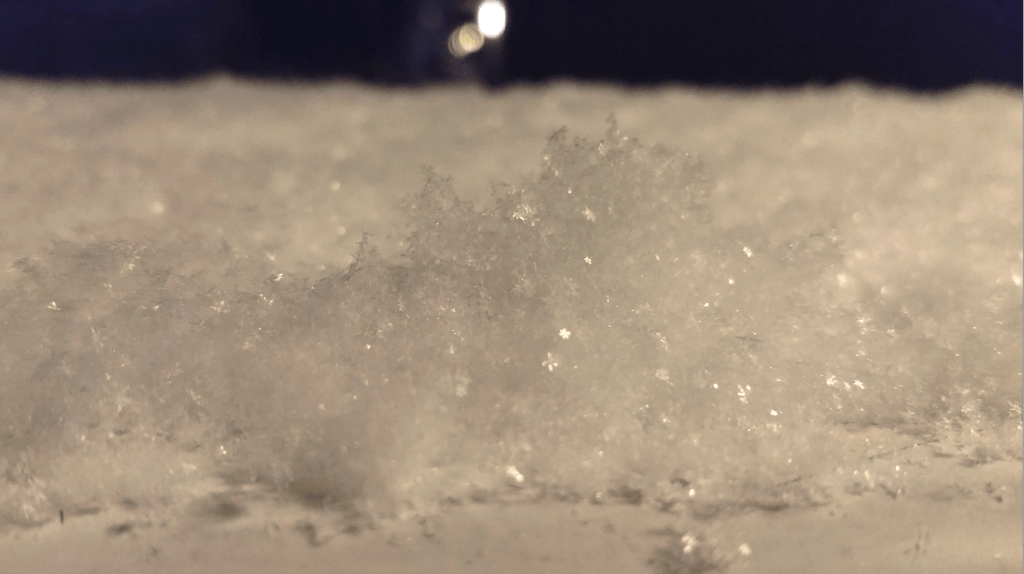

Cover Image: Snow crystals on a letterbox, Munich, 2022. Photograph by author