By Alex White (@alex_j_white)

In December 1959, the Zanzibari Rajab Saleh Salim arrived in the Soviet Union in search of work. For the 25-year-old Salim, this journey into the heart of the Cold War was only the latest example in a long line of radical and anti-colonial placemaking. Born to an African family in Zanzibar, Salim had been educated in India, before working as a seaman in colonial Mombasa and a secretary for the nationalist Mombasa African Democratic Union. In May 1959, he travelled to Egypt in secret to continue his nationalist activity within the African Association, an anti-colonial group funded by the Egyptian government. Through the African Association, Salim likely gained experience producing print propaganda alongside commentaries for Radio Cairo’s radio broadcasts in Swahili. After an apparent dispute with his employers, however, Salim found himself unable to work in Egypt and, after a brief period of wandering, found himself in the Soviet Union. There, Salim appears to have built on his existing work as an anti-colonial propagandist. By February 1960, Salim had become the first announcer of a new Radio Moscow service for East Africans in Swahili.[1]

Salim was not alone in his use of radio to the ends of anti-colonial activism. By the early 1960s, radio had become one of the most important tools for political communication in East Africa. While newspapers and pamphlets were typically limited to wealthy, literate, and urban consumers, radio broadcasting was accessible, comprehensible, and populist. Shortwave broadcasting also made it possible to transmit broadcasts across borders with ease – a fact which made radio particularly important as a tool of international propaganda. By 1961, East Africa had become the target of international radio broadcasts in Swahili from Cairo, Delhi, Moscow, Accra and Beijing, each attempting to build support for anti-colonial causes and undermine British rule in the region. In each case, however, these international radio services were reliant on East African employees as writers, translators and announcers – participant broadcasters who could lend credibility and authenticity to their programmes. Britain, Egypt, and the United States could all draw on established populations of East African students. Communist states could only attract a comparatively small contingent of students and political exiles. This gave East African collaborators a disproportionate influence over the conduct of communist broadcasters. Rajab Saleh Salim’s arrival in 1959, for example, seems to have facilitated Radio Moscow’s first broadcasts in Swahili – the first communist broadcasts produced in an African language and for an implicitly East African audience. In China, similarly, the Zanzibari anti-colonial activist Miraji Mpatani Ali was co-opted to organise Radio Peking’s own Swahili-language service from 1961.[2]

Despite their prolific broadcasting, details on the lives of East African broadcasters in communist countries remain rare. International radio propaganda was often conducted in semi-secrecy, with announcers omitting the origin of their broadcasts and a times disguising themselves as ‘African’ broadcasters to wider their potential appeal. Where archival records of communist international services exist, their political sensitivity means most have yet to be declassified for researchers. However, traces of broadcasters’ work across the colonial archive paint a fascinating picture of their mobile and radical lives. Rajab Saleh Salim was certainly closely monitored by the Zanzibari and Kenyan intelligence services, whose archives were hidden by the British government after decolonisation but were declassified after a prolonged court case in 2011.[3] Miraji Mpatani Ali is perhaps most famous today for his conversations with Mao Zedong, but he and his wife frequently appear as ‘East Africa experts’ in transcripts of Radio Peking broadcasts. These transcripts, mainly assembled by the BBC for the purposes of counterpropaganda, also give tantalising hints about the lives of other East Africans featured on communist broadcasters – from enthusiastic Somali students complaining about the Moscow weather to a Kenyan seminary student, James Ochwata, who declared himself head of the ‘Coptic Church of Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda’ and produced a series of broadcasts for Radio Moscow on the colonial government’s hostility to religious freedom.[4] These traces each bear the marks of British colonial knowledge-making. In the colonial archive, East Africans typically only appear when they begin to threaten British interests and are quickly forgotten when British priorities move elsewhere. Nevertheless, the careers of activists like Salim demonstrate the importance of mobile and transnational anti-colonial networks to radical activists, which have been too often forgotten in nationalist histories of decolonisation.

However, these traces of East African broadcasters also show that international broadcasters in Moscow and Beijing operated under tight political constraints. Zanzibari broadcasters in Beijing were obliged to read texts written by Chinese Communist Party propagandists, even if that required translating the original Chinese text into English so that it could then be retranslated from English into Swahili.[5] While East African students gave a rosy impression of studying abroad on Radio Moscow, too, memoirs reveal the extent of the discrimination and racial violence faced by Black students in communist states. In Beijing in 1962, a Zanzibari student attempted to enter a Chinese hotel and was brutally beaten by hotel staff. When two more Zanzibaris attempted to intervene – both employees of Radio Peking – they were also beaten and ultimately hospitalised.[6] In the Soviet Union, too, protests at the deaths of African students in apparently racist circumstances prompted the return of many East African students to their home countries.[7] Rajab Saleh Salim himself returned to Kenya in the autumn of 1962, claiming to be ‘disillusioned with the communist image’.[8] Somewhat typically, British colonial authorities seized upon this fact and attempted to turn East African dissatisfaction into a tool for undermining communist propaganda in the region.[9] However, the British believed Salim to be too unreliable to be of any use in British propaganda, referring obliquely to ‘non-political’ controversies in Moscow.[10] As such, traces of his life in the colonial archive disappear after his return to Kenya.

Tracing the lives of East African broadcasters in Moscow thus reveals a dynamic and engaging community of political radicals – students, exiles, communists, and nationalists who travelled far beyond the borders of their home countries to undermine the foundations of colonial rule. In some ways, these broadcasters appear to have been vital and dynamic component of communist international broadcasting. However, the mobility of these broadcasters and their importance to communist information work could not always protect communities of transnational activists from the international inequality which their broadcasts aimed to undermine.

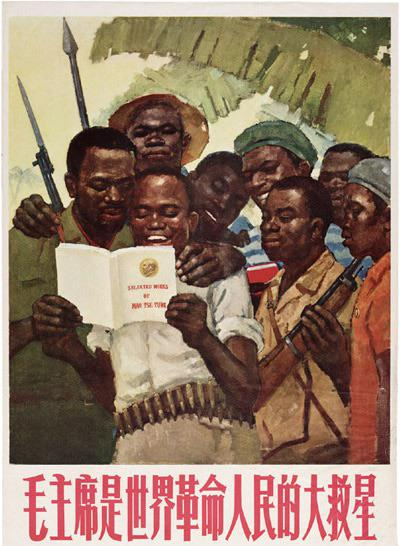

Featured image (and above): ‘Chairman Mao is the great liberator of the world’s revolutionary people’, Chinese poster from c. 1968, available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/iisg/4699046923 under a Creative Commons CC BY 2.0 license [cropped].

[1] ‘Kenya Connections with the Kenya Office, Cairo: Review of the Period 1.7.59-30.9.59’, Records of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and predecessors, National Archives, Kew [hereafter FCO] 141/6291/68; ‘Kenya Connections with the Kenya Office, Cairo: Review of the Period 1.10.59-31.12.59’, FCO 141/6291/75/1.

[2] Mao Zedong, ‘Conversation With Zanzibar Expert M.M. Ali And His Wife’, 18.6.1964, available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-9/mswv9_22.htm [accessed 6.12.2022]; ‘Chinese Communist Influence on East Africa, 6.8.1960’, FCO 141/7090/21.

[3] Riley Linebaugh, ‘Colonial Fragility: British Embarrassment and the So-called “Migrated Archives”’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 50.4 (2022), pp. 729-756, at p. 731.

[4] ‘Broadcasts in Somali’, 25.12.1961, BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, Part I: USSR [hereafter SWB SU] 857/a5/1; ‘East African Church Leader Interviewed’, 5.7.1959, SWB SU/71/a5/1; ‘British Religious Persecution’, 17.7.1959, SWB SU/82/a5/2.

[5] Çağdaş Üngör, ‘Reaching the Distant Comrade: Chinese Communist Propaganda Abroad (1949-1976)’, unpublished PhD thesis, Binghamton University (2009), pp. 126, 131n373.

[6] Emmanuel John Hevi, An African Student in China (London: Pall Mall Press, 1963), pp. 162-164.

[7] Eric Burton, ‘Decolonization, the Cold War, and Africans’ routes to higher education overseas, 1957-65’, Journal of Global History15.1 (2020), pp. 169-191, at p. 185.

[8] ‘The Traffic in Kenya Students to Communist Countries, 1st August – 31st October, 1962’, FCO 141/7141/56.

[9] P.S. to H.E., ‘People’s Friendship University for Students in Moscow’, FCO 141/7141/18.

[10] ‘The Traffic in Kenya Students to Communist Countries, 1st August – 31st October, 1962’, FCO 141/7141/56.

GReat post, thank you. I glad to see this kind of website.