interviewed by Jake Bransgrove, @Jake_Bransgrove

Historian Highlight is an ongoing series sharing the research experiences of historians in the History Faculty in Cambridge and beyond. For our latest instalment, we sat down with Benjamin Iago Gibson, a first-year PhD candidate at Trinity Hall, to discuss mountains and their roots, Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, and conceptions of time in the Medieval landscape.

Ben – can you tell me what you’re currently researching?

I can, yes. I’m interested in the way that people in the Middle Ages, particularly in Britain, thought about History and the past, and how they interacted with the material remains of that past in the landscapes around them. There’s this moment of particular interest to me in the twelfth century in England, with a generation of men who have come in just after the Norman conquest, who are English—or at least born to England—but who have a very ambiguous relationship with its past. These are, say, men in monastic foundations being threatened by the new order, by new Norman abbots, and changes in the religious tradition. And so there’s this new generation of Anglo-Norman writers; of Welsh writers; of sometimes Anglo-and-Norman-and-Welsh writers, who are trying to work out their own personal relationships with the newly-reshaped present and past of Britain, as well as their institutions’ and nations’ relationships to that history.

So I’m interested in that in a general sense, and in particular how material remains of the past got dragged into it. Imagine: you’re this second-generation Anglo-Norman, looking to try and establish a relationship to the landscape that you live in. How is this changed, how is it shaped by, say, the presence of a neolithic monument on the hill above you, or your plough turning up a horde of Roman or Anglo-Saxon coins? And, more broadly, another flange of my research looks at how people in the Middle Ages thought about the subterranean world in general – that which is buried, the world beneath their feet. But, yeah, broadly how people thought about the past, the buried past. To whom, if you like, did medieval Britain’s ‘heritage’ belong?

How did you come to this topic?

Straight through research, actually. I’ve been bound to Cambridge for quite a while now. As an undergrad I was convinced I was going to be an early modernist. I had lots of highfalutin’ ideas about doing seventeenth century political thought, and the Civil War, and seventeenth-century political and social history generally. So I diligently took all of the early modern papers, and then was given a supervisor who was a Tudor expert, so did the Tudors by mistake. And I just kept falling back from there, because doing the Tudors brought me into the Reformation, which brings you into the medieval pre-history of the early modern period, and that I fell in love with.

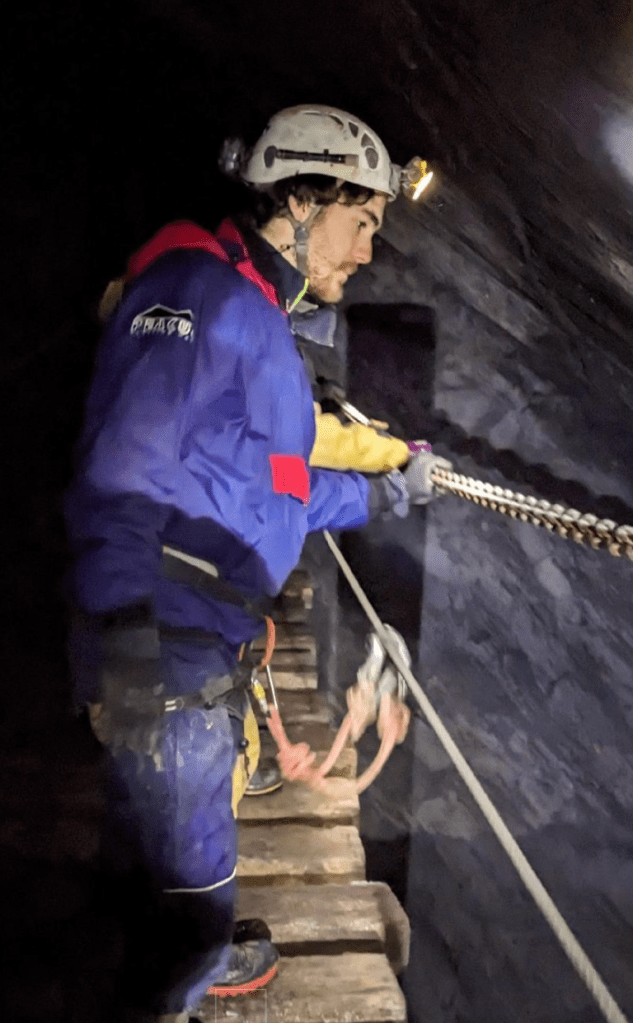

I then took a paper in my third year about perceptions of wilderness in the Middle Ages. I wrote about an awful lot of wild fenlands, forests, and deserts (in a spiritual sense) in the imaginative landscape of Britain and Western Europe, before I realised that I hadn’t written much at all about the things I thought of as wilderness in the landscape around me at home – I’m from North Wales, and there it’s all about mountains, and heath. So I set off on an MPhil, looking at the place mountains inhabited in the imaginarium of the Middle Ages. What I realised was that people in the period weren’t as interested in imagining mountains as spaces that go up, but as things that go down. So they’re really interested in the roots of mountains, and in crevasses, caves, and tunnels. It’s one of those things that, when you start to notice it, you see everywhere. You see it in romances, in chronicles, and in collections of marvels. And it’s the same motif that comes up over and over again—that these spaces have really weird relationships to time.

There’s a very famous episode, recorded by Walter Map in his eclectic collection of marvel stories and history anecdotes, De nugis curialium (The Trifles of Courtiers). The manuscript source itself is quite difficult to suss out, but lots of people write about this episode, and it keys into lots of other folklore motifs, if you like. But it runs that there was a king, named Herla, who was invited by this mysterious ‘pygmy’ king, he’s called, in this source, who comes to visit him in his court and comes to invite him back to his own realm.[1] He follows the king into the face of a cliff. The cliff sort of opens up. And he travels through the underground into a cavern with jewel-encrusted ceilings, this mysterious otherworld, and he stays there for a while with his men. When the time comes for them to leave, they exit, and the first person they come across is this peasant. King Herla says, ‘Sorry, do you know where we are?’. And the peasant says, ‘Ah sorry, you’re speaking in a tongue no one has spoken in this land for hundreds of years.’ And so he, Herla, says, quite naturally, ‘What are you on about?’ And they realise that Herla’s a Briton, and he’s come across a Saxon, that hundreds of years have passed while he’s been underground and the face of Britain has changed entire; and so Herla is condemned to wander the world, forever out of time.

Medieval history brings with it an especially rich and crowded historiographical tradition. Are there any particular writers, studies, or texts that have been especially influential in the way that you think about your topic in new ways – perhaps in relation to environmental history?

There are some. In the field of medieval studies, broadly, it comes in large part out of literary studies – ecocriticism has picked up in rather a large way in the discipline. Some of the formative works in my thinking process while I was coming up through writing about ideas around wilderness were books like Corinne Saunders’ The Forest of Medieval Romance, which is one of the things that introduced me, I suppose, to this way of typifying specific landscapes in the medieval world, that there are certain motifs and associations that are ascribed to certain landscape features.[2] That was quite formative early on. Sebastian Sobecki has done similar work on the connotations of seascapes in the Middle Ages.[3] My very first thought when formulating the MPhil was ‘right, well I’m going to do the same thing as this, but with mountains’.

A lot of work as well has been done in literary studies on the idea of the ‘otherworld’. I think about this a lot when considering these underground spaces; notably a book by Aisling Byrne called Otherworlds: Fantasy and History in Medieval Literature, about precisely this sort of thing.[4] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen is another scholar who’s written a rather lovely, lyrical book called Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman, about stone as a physical substance in the Middle Ages, and its ability to invoke vast, geological spans of time which annihilate any human perspectives of history, lifespan, or physical endurance.[5] So though the ecocritical turn has come in a big way in medieval literary studies, there’s a focus in particular on vernacular texts—it’s infiltrated a bit less in some ways into the historiography on Latinate history and hagiographical writing. This is in large part because the scholars working on these topics would often come from very different academic places. Those working on vernacular texts might have normally come up through a ‘modern and medieval languages’ or an ‘English’ route, and these bits of capital-T Theory are one of the things that get inculcated. But I’m trying to bring a bit of that kind of sensibility to the study of some Latin texts which haven’t always benefitted in the same way, working with the language, reading the language in a different way.

But at the same time, another great influence on my thinking has been the work of an archaeologist at Durham named Sarah Semple, who’s written fantastic reams about the re-use – in settlement, burial, culture, and warfare – of ancient sites in the landscape in early medieval Britain, and all from an archaeological and material perspective. That’s a viewpoint I want to incorporate into my research too—the physicality of the past, its sitedness in the landscape; the past not just as text.[6]

You alluded to some of the problems you’ve had in terms of the paucity of the sources, perhaps with regards to underworlds. Could you speak about what you mean there?

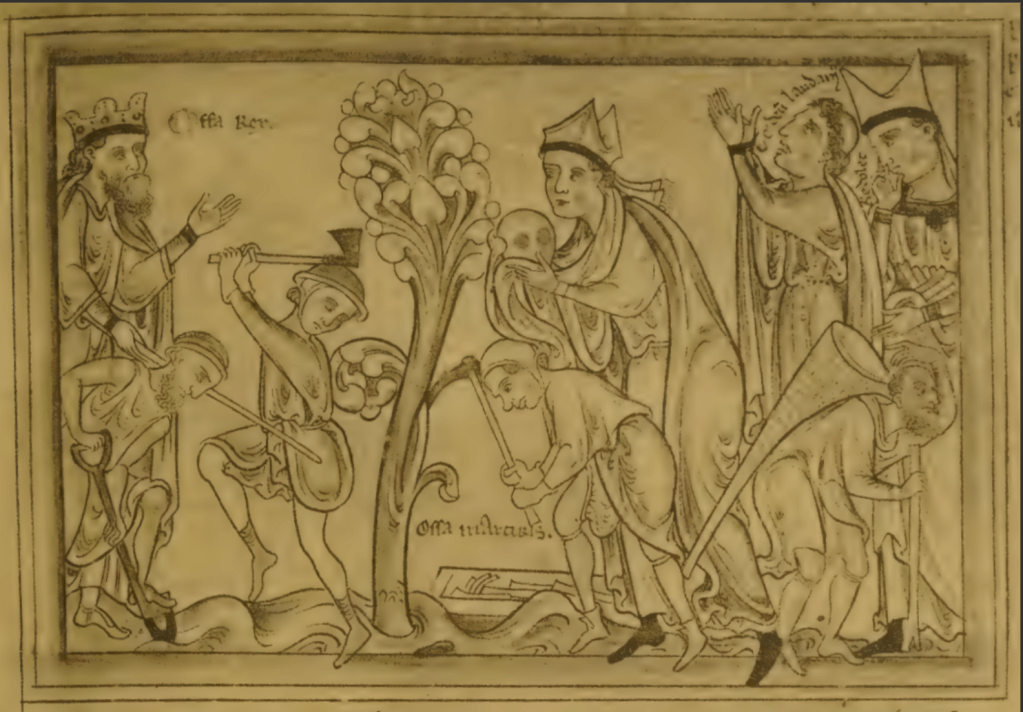

Well, actually, it’s not a paucity at all, it’s the very opposite! Working out what’s there is a matter of triaging. There’s so much. For instance, I’m partly looking at Latinate encyclopaedists; Seneca has a fun work called Naturales quaestiones (The Natural Questions), which gets read quite a lot later in the medieval period.[7] He has these passages, in common with other encyclopaedists, where he goes looking for explanations for earthquakes and volcanoes; and how it is that rivers can run down to the sea, and the seas don’t fill and the rivers don’t empty. The answers are all in this image of a vast network of underground passages, which connect every corner of the world: through which air travels and gets caught and bursts through and shakes the earth above; through which currents of fire travel; in which stones and gems are born; through which water travels back up from the seas to the tops of mountains. He has this fantastic passage which really sets my imagination going, let alone anyone reading it in the twelfth century, which goes – I’m paraphrasing roughly – that everything you see above, you find below: under the earth there are vast mountains and caverns, chasms falling away into enormous underground lakes and massive halls. It’s the idea of there being a second earth beneath the earth, which gets picked up over and over again. If this sounds disordered, it’s because it is disordered in my mind at the minute. Making an order of it has been a job so far. I’m also looking at artistic representations of the discovery of relics buried under ground, artistic depictions of hell underground. The way that you’ve got this odd stratigraphy between the dead who are buried at a ‘shallow’ level, who await resurrection, then you’ve got the real depths, the abyssal hell…

Closer to the surface are sources that are important to my work and made available through a particular legal quirk. Thanks to the Crown prerogative over finds of treasure in Britain – which can be traced in the legal record at least as far at the reign of Henry II in the twelfth century, but which goes back much further – it’s required by law (as it very much still is, and in Scotland the King has a claim on that Saxon brooch you dug up in the back garden) to report all instances of the discovery of buried treasure to the relevant authorities. This means that in the legal record, you start to get instances where, now and then, amidst the business of the day, the official rolls of escheat might mention that So-And-So Smith found a hoard of a thousand silver coins under a barrow in the parish of Such-And-Such, and that he was guided to them by the magical aid of an aerial spirit, called upon through the glass of a mirror. So I’m also combing the legal record to get behind the literary sources, if you like, and get a look at what fragments of the past people in the Middle Ages were actually coming across in the landscape around them, how they responded to them, and what beliefs they attached to them.

When you start picking up on these sources you realise that you’ve always known them; that you’ve always known this is the case; and anyone who’s drunk deeply of the Middle Ages also knows it instinctively. It’s the reason why in Tolkien all the mountains have under-realms, Kings-under-Mountains; the reason why when Gandalf fights the Balrog they descend thousands and thousands of fathoms underground, and fight from the lowest depths to the highest peak.[8] C.S. Lewis, in The Silver Chair, one of his Narnia books, has the characters travel through this vast underground space where they encounter a sleeping giant from a primordial age called Father Time.[9] Anyone who’s been exposed to this material knows it’s there, it’s putting it in order that has been the great work so far.

Shifting gear, are there historians practicing today or in the past who you admire?

Lots of the work that I’m doing at the minute – writing about chronicle writers of the twelfth and thirteenth century – has a long pedigree, which goes back at least to the mid-nineteenth century, to titan editors like William Stubbs, Regius Professor of Modern History and Bishop of Oxford from the 1860s, and blokes who edited an awful lot of British Latinate material, into these – some still definitive – editions, in the Rolls Series. I have an enormous soft spot for some of these figures, especially for those from the later twentieth century, involved in the second round of that process, editing the next generation of the works.

But then I also admire so many of the men they were editing, the Latin writers themselves, with their antiquarians’ eyes and classical pens, and their gossiping and their theorising, their ulterior motives and their rampant personalities. The world of history writers and historians in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries can be an incredibly personal one. There are individual men who stand behind all of these works, men very much shaped by their times, who are sometimes known to us in large part only through their writings. And every so often they’re also (which makes them so much better) fantastic idiosyncratic prose stylists.

I’m a massive sucker for history writing that’s also great prose. Sir Richard Southern delivered a lecture series to the Royal Historical Society over four years in the seventies, published in the Society’s Transactions afterwards, which has sort of almost magisterial overviews – and in absolutely fantastic style – of the practice of medieval history writing, and of the influences on that writing, and on what this reveals of medieval perceptions of History-with-a-big-H.[10]

But these scholars who have immersed themselves in the material to the point where they know each of the writers, works, and deeds of the period intimately, who know where they were, what their influences were, and can divine something almost of their inner workings of their hearts and minds – people like Antonia Gransden; like Michael Winterbottom and Rodney Thomson, who did a lot of work on a twelfth-century historian I focus an awful lot on named William of Malmesbury.11 Anybody in that sphere I have an enormous crush on, really. It’s their work I read and think I would quite like to get to that level of utter familiarity and comfort and fish-in-waterness with this body of material. That’s what spurs me on.

This is your first year of the PhD – what would you say the biggest problems or difficulties have been so far?

I took some time out between my master’s and PhD, so one of the things has been settling back into the rhythm of term – and term in a new sense, because many of my undergraduate years, and to a degree my master’s year, were blighted by Covid, so it’s just been having my first normal Cambridge year since this time four years ago. The rhythm of academic life, too – I’ve been trying to make myself to go into lectures, to plug into it all. It sounds odd to say but one of the big difficulties has been just easing back in after some time away. The other thing, which I’ve just talked about, is source management. It’s all very well to identify what’s there, but identifying what’s important has been taking up so much headspace recently that I almost haven’t been able to plunge as deeply into any individual body of sources as I’d like; I’ve been too busy drifting between them, putting them into a pattern. It’s funny, none of my massive problems so far have been conceptual, they’ve all been incredibly prosaic. Another one is working out a healthy and effective system of note-making which will endure me three years and potentially an academic career afterwards. That’s been the real Augean Stables of the last five months.

One last question: what do you think is unique about the Cambridge experience for a postgraduate historian?

Sometimes you feel like you are sitting in the cockpit of the historical space shuttle and beneath you is a thousand gallons of high octane source material. It’s a silly smug feeling that can come over you – me, really – when you read some of these editions of texts and you’ll run through the list of manuscript sources and you find that half of them could be available to you if you sent off an email to the Wren Library or Parker Library, or to the University Library. That’s really quite wonderful.

I’m an enormous fan of the college system, too. I’m the product of two of Cambridge’s smallest colleges, and I think that while being a PhD student can sometimes be a fantastically lonely and isolating experience, one of the greatest buffers which Cambridge is able to put between you and that is the college system and the sense of community that brings about. In different ways, I owe both the colleges that I’ve been to an enormous amount. And I don’t think I’d have come through any of my degrees half so well without them.

Images:

Fig. 1 & Cover Image. Headshot.

Fig. 2. Ben, a few hundred feet below a Welsh mountain. Photo provided by the interviewee.

Fig. 3. Silver miners hard at work beneath the earth in the early sixteenth-century Kutná Hora cantional (Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek MS. Mus. Hs. 15501, fol. 1v)

Fig. 4. The dragon Smaug and his hoard, from J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937)

Fig. 5. The discovery of the relics of St Alban by King Offa, as depicted by Matthew Paris in his 13th-century Vie de seint Auban (Trinity College Dublin MS 177, f. 59v)

Notes:

[1] Walter Map, De nugis curialium, trans. M. R. James (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983).

[2] Corinne J. Saunders, The Forest of Medieval Romance: Avernus, Broceliande, Arden (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1993).

[3] See Sebastian I. Sobecki, The Sea in Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008).

[4] Aisling Byrne, Otherworlds: Fantasy and History in Medieval Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[5] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (Minneapolis, MI and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

[6] See Sarah Semple, Perceptions of the Prehistoric in Anglo-Saxon England: Religion, Ritual and Rulership in the Landscape (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[7] Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Naturales quaestiones, trans. Thomas H. Corcoran (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971).

[8] J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (London: Allen & Unwin, 1954), ch. 5.

[9] C. S. Lewis, The Silver Chair (London: Geoffrey Bles Ltd, 1953), ch. 10.

[10] R. W. Southern, ‘Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing: 1. The Classical Tradition from Einhard to Geoffrey of Monmouth’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 20 (1970), pp. 173-96; idem., ‘Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing: 2. Hugh of St Victor and the Idea of Historical Development’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 21 (1971), pp. 159-79; idem., ‘Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing: 3. History as Prophecy’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 22 (1972), pp. 159-80; idem., ‘Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing: 4. The Sense of the Past’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 23 (1973), pp. 243-63.

11 See Antonia Gransden, Historical Writing in England, c.550 to c.1307 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974), and Historical Writing in England, c.1307 to the Early Sixteenth Century (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982); Rodney M. Thomson, William of Malmesbury (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1987, revised edition 2003).